Oil & Gas 360 Publishers Note: This is an excellent summary of some of the natural gas dependencies and geopolitical problems it involves. What the article is missing is the new players to this evolving drama with potentially disastrous results. Turkey, and others, have started on a mission to become energy independent. The new discoveries of large natural gas in the Mediterranean and Baltic have opened major issues around territorial waters to the edge of war. We are covering the implications in upcoming stories.

A natural gas pipeline being built under the Baltic Sea from Russia to the German coast is shaking up geopolitics. Nord Stream 2, as it’s called, fuels worries in the U.S. and other countries that the link could give the Kremlin new leverage over Germany and other NATO allies. As the project neared completion, U.S. sanctions and calls for European restrictions have left the construction in limbo as political tensions with Moscow mounted.

1. What is Nord Stream 2?

It’s a 1,230-kilometer (764-mile) gas pipeline that will double the capacity of the existing undersea route from Russian fields to Europe — the original Nord Stream — which opened in 2011. Russia’s Gazprom PJSC owns the joint Russian-European venture, with Royal Dutch Shell Plc and four other investors contributing half of the 9.5 billion-euro ($11.2 billion) cost. Initially expected to come online by the end of 2019, the link has been delayed by U.S. sanctions that forced Swiss contractor Allseas Group SA to withdraw its pipelaying vessels. The pipeline operator is looking for solutions to lay the remaining 6% of the pipe, which includes construction work in Denmark’s waters.

2. Why is it important?

The pipeline will help Germany secure a relatively low-cost supply of gas amid falling European production. It’s also part of Gazprom’s decades-long effort to diversify its export options to Europe as the region moves away from nuclear and coal. Before the first Nord Stream opened, Russia was sending about two-thirds of its gas exports to Europe through pipelines in Ukraine. Their troubled relations since the Soviet Union collapsed left Gazprom exposed to disruptions: A pricing dispute halted gas flows through Ukraine for 13 days in 2009. Since then, relations between the two countries have worsened, culminating in the Ukrainian popular revolt that kicked out the country’s pro-Russian president and led to Russia seizing the Crimean Peninsula.

3. Who’s opposed to Nord Stream 2?

In August, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s administration came under pressure from German lawmakers to back away from the project after the poisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny heightened diplomatic tensions. She has repeatedly sought to de-politicize the pipeline by calling it an economic project. The plan has also been opposed by Ukraine, Poland and Slovakia — countries that sit between Russia and Germany and collect transit fees on the natural gas that flows through their territories. Those concerns were partially alleviated after Gazprom reached a deal to continue gas transits via Ukraine through at least 2024.

4. Why is the U.S. involved?

U.S. President Donald Trump and members of the U.S. Congress say that Nord Stream 2 will make Europe overly dependent on Russia. Trump has said that Germany in particular will become “a captive to Russia.” It’s also clear that the U.S. is keen to increase its own sales to Europe of what it calls “freedom gas.” In June, a bipartisan group of senators proposed expanding the current sanctions against Nord Stream 2 to include insurers, certifiers and other companies working on the project. Senator Ted Cruz, one of the lead sponsors of the legislation, said the pipeline poses “a critical threat to America’s national security and must not be completed.”

5. What do the sanctions mean for the project?

Work at the Nord Stream 2 offshore site halted in late 2019 and neither the pipeline operator, Nord Stream 2 AG, nor its parent company Gazprom have announced a new construction plan. However, earlier this year Russia sent a pipelaying vessel, Akademik Cherskiy, on a three-month journey from the east Pacific coast to Germany’s Baltic port of Mukran where Nord Stream 2 stores its pipes. In August, Damark’s permission to use pipelaying vessels with anchors for construction of the link came into force, expanding Gazprom’s options for completion. Pressure testing, cleaning, and filling the link with buffer gas may take six to seven weeks after the link construction is completed, based on the schedule for building the original Nord Stream. In June, Gazprom reiterated its plan to start gas shipments via Nord Stream 2 in late 2020 or early 2021. However, tighter U.S. sanctions could put that timetable in doubt.

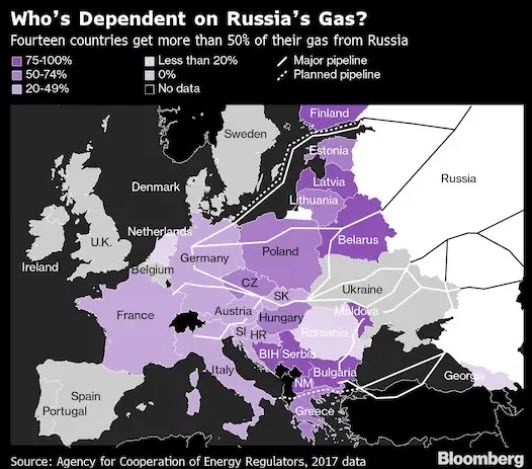

6. Is Europe really captive to Russian gas?

The European gas market has become more competitive as liquefied natural gas, or LNG, vies to replace declining local production from the North Sea and the Netherlands. Gazprom estimates that in 2019 its share of the European market was 35.5%. The company’s domestic rival, Novatek PJSC, is also expanding its LNG sales in Europe. But not all countries are equally dependent on Russian imports. Gazprom remains the traditional key supplier for Finland, Latvia, Belarus and the Balkan countries, but western Europe gets gas from a wider range of sources, including Norway, Qatar, African nations and Trinidad. More nations, from Germany to Croatia, are seeking to build LNG import terminals to accept shipments from around the world.

7. Will the U.S. sell more gas to Europe?

Before the Covid-19 pandemic slashed global fuel demand and sent prices to record lows, the U.S. was a significant supplier of tanker-borne gas to northwest Europe. But U.S. fuel must be chilled into a liquid form and shipped across the Atlantic at great cost. Russia is transporting its gas mostly through the world’s largest network of pipelines that have been in place for decades. This year transatlantic LNG shipments have become even less economic. Yet U.S. suppliers are focused on long-term prospects, and have had some success securing deals with Poland. More broadly, they have to hope for a resolution of the trade war between the U.S. and China, whose imports of U.S. gas have slumped since the government in Beijing applied tariffs in retaliation to levies imposed by the White House. The International Energy Agency expects the U.S. to become the world’s biggest LNG seller in 2025.