“Having this kind of debt is a killer”: FCX’s CEO Adkerson – Q1’16 conference call

Mining giant Freeport-McMoRan (ticker: FCX) is known internationally as the world’s largest copper miner—one that would be happy right now if it can sell its oil and gas assets for $3 billion cash, even though that price represents an 85% haircut from what the company originally paid for them.

The Phoenix-based company is the world’s largest publicly traded copper producer and the world’s largest producer of molybdenum. It also has significant gold production and cobalt interests.

But like oil, times are tough for those other commodities—copper is way down. High grade copper was at $391.35 per ton five years ago. Today it’s $292.90. Gold has dropped in the same period from about $1,800 to $1,265 per ounce. Molybdenum dropped from $15 to $5 per pound. Cobalt went from $37,000 to $23,500 per ton.

FCX’s oil and gas assets for sale

With a $20.8-billion debt albatross weighing on the company as of the end of the first quarter of 2016, word went out in December 2015 that Freeport was looking for a buyer for its oil and gas assets. $20 billion of debt represents a large obligation of cash flow. The 2015 interest payments by FCX amounted to $645 million. In the same year, FCX paid $120 million in cash dividends and other distributions were paid to non-controlling interests. FCX was obligated to payout 20% of its cash flow to service debt and equity holders in 2015.

How did this much debt get onto the FCX balance sheet?

It was only four years ago that FCX acquired its oil and gas namesake, McMoRan Exploration (ticker: MMR) and Plains Exploration and Production (ticker: PXP) in a cash and stock swap valued at $19.6 billion, which included the assumption of both companies’ debt. In the third quarter of 2012, before the transaction was announced, FCX had $3.5 billion of debt, which was about 9% of its $41 billion enterprise value.

Pro forma for the deals, the debt to enterprise valuation ratio ballooned to 41%.

It was a combination that made sense at the time, for the times

McMoRan Exploration was a renaissance exploration company. A co-founder back in 1969, James R. Moffett, aka Jim Bob Moffett, was a world renowned wildcatter for oil and gas and minerals deposits. During the years when he presented at EnerCom’s The Oil & Gas Conference® in Denver, it was standing room only. Other oil and gas executives would cut short their one-on-one meetings with investors to hear Jim Bob Moffett talk about the “shallow-deep” Gulf of Mexico.

Moffett saw the acquisition of shallow-deep assets as Freeport-McMoRan’s foot in the door with natural gas. “If you look at what’s going on around the world, especially after the tragedy in Japan with the nuclear plants that got destroyed during the tsunami, and you realize that that has created a negative reaction to the nuclear industry,” said Moffett during the conference call discussing the transaction. “Coal is under a lot of heat because of the environmentalists. So natural gas turns out to be the cleanest energy form.”

During the same conference call on December 5, 2012, Freeport-McMoRan president and CEO Richard Adkerson explained the deal would position the company to take advantage of commodities growth.

“With these transactions, we believe that we will be creating a larger, more diverse company with an enhanced exposure to [the] global growth story and improved growth characteristics for our company,” explained Adkerson. “We believe we understand the risk and rewards associated with it.”

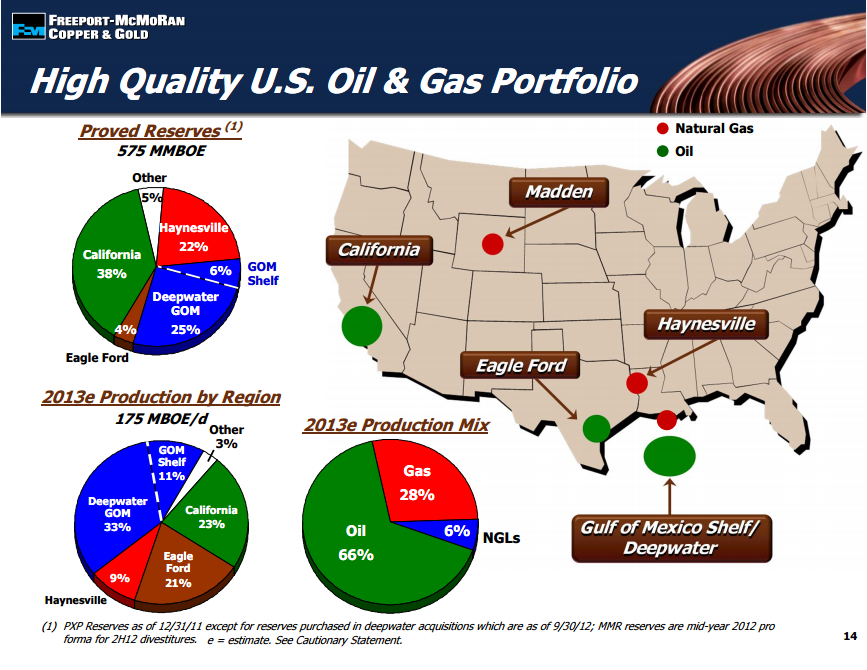

While the combination involved assets in California and other locations, one of the real prizes of the combination were oil and gas assets in the “Shallow-Deep” region of the Gulf of Mexico – described by the 2012 merger press release as “shallow water ultra-deep gas trend with sizeable potential, located offshore in the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico and onshore in South Louisiana.” Other assets for sale include onshore and offshore assets in California and properties in the Haynesville shale formation, along with other natural gas assets in Louisiana.

Another big prize of the combination was the addition of Jim Flores.

Before heading Freeport-McMoRan Oil & Gas LLC as the company’s chairman and CEO, James Flores headed PXP. During Flores ten-year tenure, PXP saw production and proved reserves grow 420% and 174%, respectively.

What went wrong?

That’s the question. An acquisition or a merger of companies works when the assets fit. When disparate assets are put together, such as Mobil Oil buying Montgomery Ward in 1976, any down-cycle will add pressure when each asset base has a strong and independent management team. PXP was public and had its team. Same for MMR and FCX. So why the merger?

Moffett

“[The acquisition] gives us not only a chance to put together one of the biggest natural resource companies in the world, as oil and gas are already a diverse commodity and, of course, the USA assets that we’re in, make us about a 50% USA and 50% foreign asset,” Moffett said in 2012.

“So we think we have put together a combination of companies that will allow us to be able to look at and evaluate any natural resource play, whether it’s mining or oil and gas, and make sure that we’re looking at the investments that will bring the most value to the shareholders.

“I think when you have a chance to realize what a trove of treasures, a trove of assets that we’ve brought together and [how] the management team now in this company will be able to manage the assets … it’ll be an unbeatable combination to have this multinational, multi-resource company to continue to provide the values that we have provided,” said .

Flores

Speaking about the assets that came with the deal, Flores said the oil and gas side of Freeport-McMoRan’s business would keep pace with double-digit growth on the mining side. “It’s going to be my charge to make sure our unit growth is neutral to positive to the mining growth,” said Flores.

“One thing we were very concerned about was the dilution of our mid-teens growth rate, somewhere in the 12% to 15% growth rate, we think we [will] have with our current assets through the end of this decade… And I think we have the assets to do that, not only through the end of the decade, but with the exploration drilling, we’ll have them long term.”

Not all investors were pleased with the new treasure trove—some gloves came off

While Freeport-McMoRan had a history of successfully buying large assets and paying down the debt incurred in the acquisition, not all of FCX’s investors were pleased with the deal. During the Q&A portion of the company’s conference call, Evy Hambro, the lead manager of BlackRock’s World Mining Fund and World Gold Fund, which were invested in the mining giant, came out of the gate swinging.

“Hello and congratulations on making one of the worst teleconferences I’ve ever heard to justify a deal,” he said after being connected. “Before I ask my question, would it be possible to find out if anybody on the call from your side is not conflicted in answering the question I want to ask,” he asked, referring to intertwined relationships between FCX’s management and the management at Plains.

“Most transactions we’ve seen in the past, that have tried to justify themselves based on the growing their size or through diversification, haven’t worked,” said Hambro. “Investors obviously have the freedom to diversify their own portfolios by commodity and by geography and don’t need management teams to do it for them. Can you tell us why this is going to be different this time?”

Hambro continued: “We have a situation where we can choose today to be shareholders in all of the companies out there that are going to potentially be combined here. We don’t need Freeport to do it for us. I haven’t heard anything on this call that in any way justifies why these companies should be put together, and I find it incredibly disappointing that as a management team, you’ve chosen to break the trust with investors from what the business was that we chose to invest in.”

Adkerson’s response indicated that the company knew it was taking a risk, but it saw it as one that would put Freeport-McMoRan in position to take advantage of growing demand for what was, at the time, a high-value commodity—natural gas.

“I will tell as we look at the opportunities here from an exploration and growth standpoint, through Plains and what they’re doing in the deep-water, … [we see] relatively high cost production that at today’s prices earns significant margins and will do so for years,” explained Adkerson. “And then the growth in the (shallow) deep-water, the McMoRan story is one that’s interesting, high risk, very high potential and if successful, could bring tremendous amounts of gas to the market at exactly the right period of time.”

Hindsight is 20/20: fast forward to 2014-16

The oil price crash that would follow almost exactly two years later changed the landscape drastically. With the company loaded with debt that it took on to purchase the assets, and oil plummeting from multi-year highs, the PXP and MMR assets began to drag on the mining company’s balance sheet.

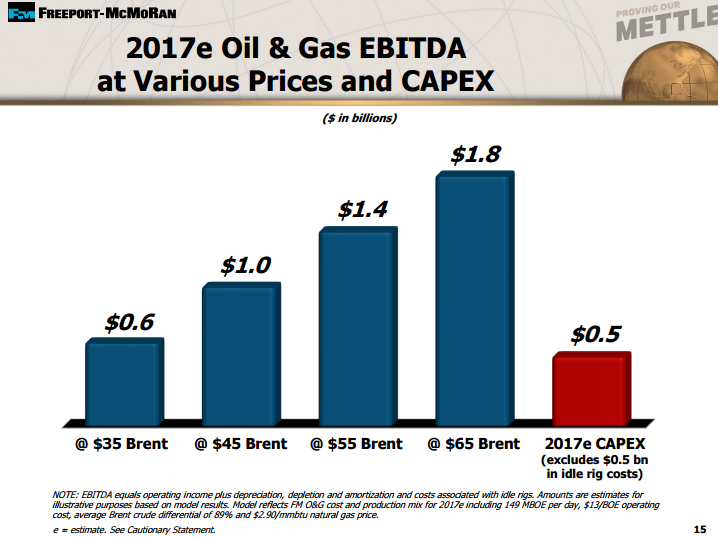

In 2014, oil and gas accounted for 20% of the company’s $21 billion in revenue. But in the first quarter of 2016, oil and gas was 2% of total revenue. For the quarter, Freeport reported a $4.2 billion loss, “primarily [due to] the reduction of carrying value of oil and gas properties, idle rig costs and other items,” Kathleen Quirk, FCX executive vice president and CFO said during the company’s conference call.

The company reported consolidated debt of $20.8 billion in its first quarter release. Freeport-McMoRan has total consolidated cash of $331 million, and $3.0 billion available under its $3.5 billion credit facility.

“You should not be this leveraged,” said Adkerson during the company’s most recent conference call. When prices decline as part of commodity downturn, “having this kind of debt is a killer,” he said. With negative exposure to a portfolio of falling commodities, it’s easy to see why the CEO of the $40 billion (enterprise value) company made the comment.

A small sale: FCX Sells $102 million Midland, Delaware, Wolfcamp, Spraberry assets to Black Stone

Just one day prior to its first quarter earnings release, Freeport announced that it had sold $102 million in assets to Black Stone Minerals. The package included 1.2 million gross/126 thousand net mineral acres, with estimated average daily production of approximately 850 BOEPD and estimated proved developed producing reserves of 2.0 MMBOE as of the end of 2015.

Commenting on the deal it made with Freeport, Thomas Carter, Jr., Black Stone’s CEO said in a press release: “This transaction is a great example of the type of package that Black Stone likes to acquire – a diverse set of mineral and royalty assets with existing production, near-term development opportunities, and meaningful exposure to attractive oil and gas provinces.

“The majority of this acreage is in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas and is complementary to our existing positions in those states. The package includes acreage in both the Midland and Delaware basins that is well positioned for the Wolfcamp and Spraberry intervals, as well as acreage in other resource plays. These assets will benefit from our focus on active minerals management and we’re confident that they will be strong contributors to production and reserve growth in future years.”

Black Stone purchased the assets for $120,000 on a per flowing BOE basis, almost quadruple the going Q1’16 North American M&A average of $29,638 per flowing BOE, according to data provided by PLS.

Finding a buyer: not a straight-forward process in today’s market

The next day on the company’s conference call, Adkerson discussed the difficulties Freeport is facing in finding a buyer for the rest of the company’s assets.

“We looked for potential buyers for the business during the first quarter aggressively… because of the conditions in the marketplace, with low oil prices, with credit pressures on companies from the very largest through the business with the lack of credit, we just concluded at this point that the values that might be available in sale or monetization transactions simply didn’t reflect the long-term value of these assets,” said Adkerson.

“The M&A markets are slow due to price volatility in oil prices and sellers are reluctant to sell unless forced,” Brian Lidsky, managing director for PLS, told Oil & Gas 360®. The uncertainty around what assets might be worth in six weeks or six months has left many potential sellers hesitant to let go of their properties in case their production becomes more valuable in the near future.

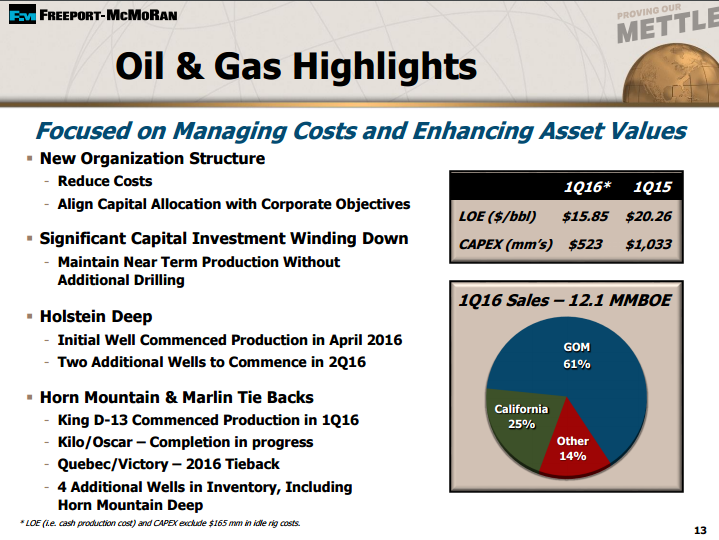

Doing just enough to maintain production without drilling

For the time being, it appears that Freeport-McMoRan plans to keep production flat without drilling any new wells. “We recently completed a series of tieback wells to our production facility. That’s going to allow us for a period of time to maintain near term production without additional drilling,” said Adkerson. In the Gulf of Mexico “we have four additional drilled wells that are in our inventory including Horn Mountain deep that we’re going to be able to bring on production without drilling new wells. That’s going to allow us to maintain production for the foreseeable future.”

No color from Freeport

Oil & Gas 360® reached out to Freeport’s media contacts and asked what FCX considered to be a fair price for its assets, and at what price the company might consider increasing production from its assets. But the company declined to elaborate outside the information in the press releases.

Freeport announced May 13, 2016, that the company canceled two drilling rig contracts with Noble Drilling, a subsidiary of Noble Energy (ticker: NBL), as it continues to look for ways to cut costs. Under the settlement, FCX will provide Noble with $540 million in value over a 30-day period payable at Freeport-McMoRan’s option in cash, Freeport’s common stock or bonds issued by Noble or its affiliates with maturities through December 31, 2019, subject to a limit of $200 million of bonds, according to a press release from Noble.

So what is the value of the Freeport-McMoRan oil and gas assets?

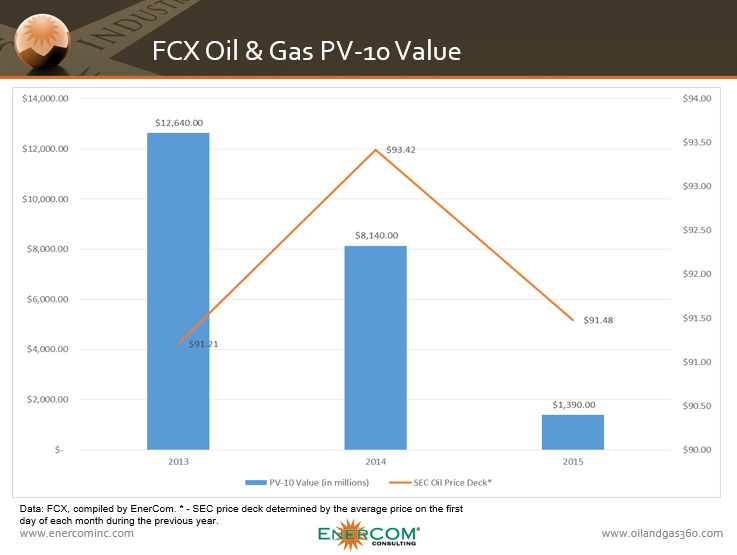

The fluctuations in oil prices make it difficult to pin down a single number that might accurately estimate the value of FCX’s oil and gas assets, but it’s clear that the company has yet to hear a bid it liked enough to part with its oil and gas operations. In its year-end 2015 financial statement, Freeport-McMoRan listed the PV-10 value of its oil and gas assets at $1.4 billion, 92% less than $19 billion the company paid for the assets, including assumed debt.

Plains reported full-year 2012 PV-10 value of $13.6 billion, while McMoRan Exploration reported a PV-10 value of $530.3 million for the same period. The PV-10 value of the combined assets just three years later was 90% less than when FCX made the acquisition.

At the time of the combination, PXP was producing 106.9 MBOEPD, and MMR produced 22.9 MBOEPD.

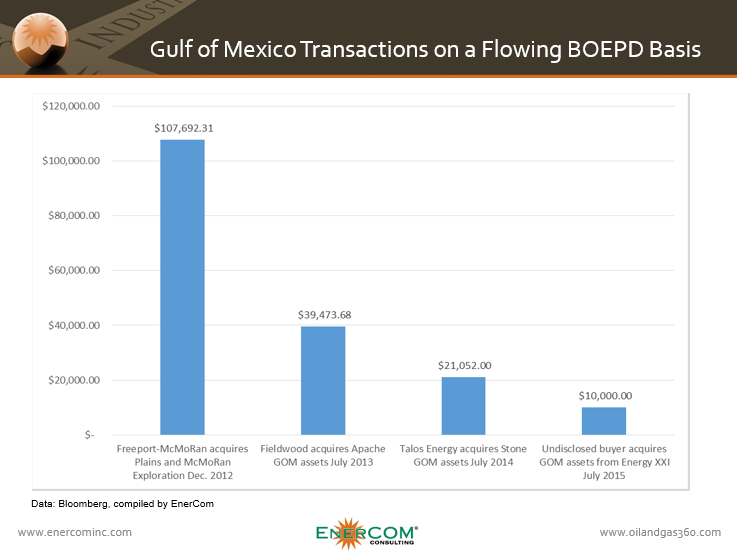

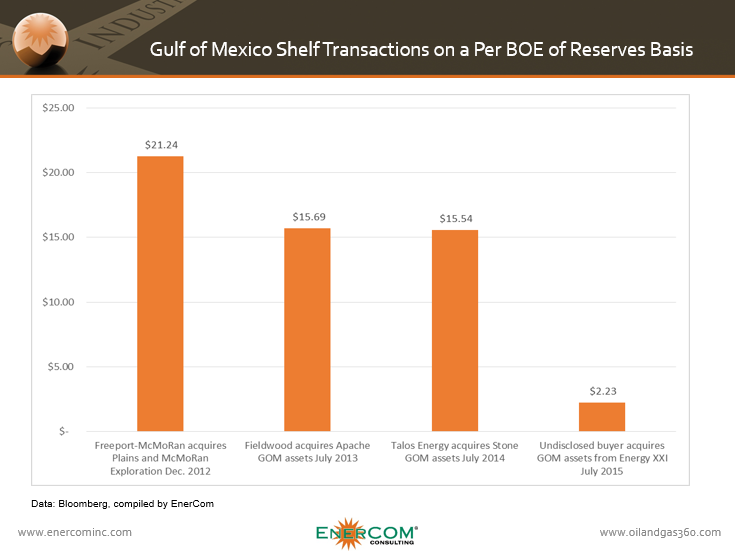

Compared to deals done in the same region in 2013, 2014, and 2015, Freeport paid a higher price for its Gulf of Mexico assets, both on a per-flowing-BOEPD and per-BOE-of-reserves basis.

Fieldwood Energy LLC, the largest operator on the Gulf of Mexico Shelf, paid $3.75 billion for Apache Energy Corp.’s (ticker: APA) GOM assets, which included 95 MBOEPD of production and 239 MMBOE proved reserves. On a per-flowing-BOEPD basis, Fieldwood paid $39,474 for APA’s assets, and $15.69 per BOE of reserves.

The most recent analogous deal took place in July 2015, when an undisclosed buyer purchased 2.1 MBOPED and 9.4 MMBOE of reserves from Energy XXI for $21 million. The deal broke down to $10,000 per flowing BOEPD, and $2.23 for BOE of reserves, reflecting the drastic downturn in oil prices over the course of two years.

Using these two deals as a high and low point for the potential value of Freeport-McMoRan’s assets still leaves a wide range for a potential price tag. But given the price of WTI in July 2013, the month the Fieldwood deal was announced, averaged $105.02, it seems likely that FCX’s assets would trend on the lower side.

Freeport-McMoRan and its oil and gas executive team part company

On April 5, 2016, Freeport-McMoRan announced that it had restructured its oil and gas arm to reduce costs. Once a separately run business segment, the oil and gas division has been put under the corporate structure of Freeport-McMoRan, the mining company.

The company announced the resignation of four executives associated with the oil and gas assets. CEO Jim Flores, President and COO Doss Bourgeois, EVP and CFO Winston Talbert, and EVP and General Counsel John Wombwell all departed Freeport, according to the announcement on April 5th.

To run things on the oil and gas side, Mark Kidder was named Executive Vice President – Operations of FM O&G, and will lead FM O&G’s operating team, according to the FCX press release. “Mark previously served as Vice President – Operations and has 36 years of operational experience in the offshore and onshore upstream energy industry, including 13 years with FM O&G and its predecessor and 23 years with major oil companies and independent energy producers.”

The mining giant said that it would further cut its oil and gas workforce by 25%, or 325 jobs, as part of its overall plan to restructure. FCX said it expects to post a related charge of $40 million in the second quarter related to the decision to cut its workforce.

Flores: a long-time oilman with a history of growing production, reserves

Jim Flores has played a central role in building a number of large oil and gas companies over the years prior to Freeport’s acquisition of Plains. Flores holds degrees in petroleum land management and finance from Louisiana State University, and has more than 25 years of experience in the oil and gas industry.

Flores held a number of top-level positions in various companies prior to Plains and Freeport-McMoRan. In 1994, he led Flores & Rucks, Inc. (Ticker: FNR), which grew to produce 24 MBOPD and 50 MMcf/d in his time at the helm. In 1996, the company was highlighted as the third-highest performing stock, increasing in value by 276% as the company continued to grow.

Ocean Energy (Ticker: OEI), FNR’s successor, merged with Houston-based United Meridian in March of 1998, at which point Flores’ company operated more than 2,500 oil and gas wells producing 120 MBOEPD. Under Flores, Ocean grew to an E&P with pre-merger annual revenues in 1998 of $550 million and approximately $2 billion in assets before merging with Seagull Energy Corporation in 1999. By January 2001, the end of Flores’ tenure as vice chairman of Ocean Energy, the company’s annual revenue exceeded $1 billion, with over $5 billion in assets reported in 2000.

Not one to sit idle, Flores quickly began his next position as chairman and CEO of Plains Resources (Ticker: PLX), which eventually spun off into PXP in December 2002. In 2004, he was also named president of the company, where he served until the company’s acquisition by Freeport-McMoRan. Under Flores’ management, production grew more than four-fold to 106.9 MBOEPD in 2012 from 25.6 MBOEPD in 2002. Reserves also increased by 74% to 440.4 MMBOE in 2012 from 253.0 MMBOE when Flores initially came on board.

Bonding costs may have caused disagreement in asset sale

The news broke at the end of December 2015 that Freeport-McMoRan planned to sell its oil and gas assets for $3 billion, generating curiosity in the industry about who was interested in buying the assets.

Speculation is, that as FCX sought to sell the oil and gas assets for $3 billion, there were no buyers willing to step up. But in discussions with oil and gas industry veterans, a familiar theme emerged that the logical buyer was Jim Flores.

Sources familiar with the matter said Flores wanted to acquire the assets into a separate entity, and that he had a financial backer for the $3 billion price tag. However, recent changes in bonding of Gulf of Mexico properties set forth by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management were an impediment to any buyer – Flores or not.

It was estimated that the bonding costs for the Gulf of Mexico assets were anywhere from $500 to $700 million, an amount that any buyer would want the seller to bear.

Oil & Gas 360® contacted Jim Flores and attempted to confirm this information and discuss his future plans, but Mr. Flores declined to comment.

Freeport aiming for $3 billion in asset sales by mid-year

The $102 million oil and gas asset sale to Black Stone, was preceded by another sale announcement—a bigger one on the copper side of the street. In mid-February, Freeport agreed to sell a 13% ownership interest in its Morenci copper mining venture to Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Ltd. for $1.0 billion in cash.

According to the news release, “As of December 31, 2015, FCX’s 85% share of consolidated recoverable reserves totaled 12.0 billion pounds of copper and its 85% share of 2015 production approximated 900 million pounds of copper. In 2015, FCX’s 85% share of Morenci revenues totaled $2.2 billion and production and delivery costs totaled $1.5 billion.” The company expects the deal to close mid-2016.

So far in 2016, Freeport has announced $1.4 billion in asset sales. In the company’s 2015 10-K, it reported “a springing collateral and guarantee trigger” was also added to its revolving credit facility and term loan.

45 days to find a buyer

“Under this provision, if [FCX has] not entered into definitive agreements for asset sales totaling $3.0 billion in aggregate by June 30, 2016, that are reasonably expected to close by December 31, 2016, [FCX] will be required to secure the revolving credit facility and term loan with a mutually acceptable collateral and guarantee package.”

During the company’s conference call, Adkerson was asked how he felt about the additional $1.6 billion needed to avoid the provision. “We really expect to meet that spring collateral test in the second quarter, very confident about that,” he responded.

On May 9, 2016, Freeport-McMoRan announced the sale of its interest in TF Holdings Limited for $2.65 billion in cash, and up to an additional $120 million contingent consideration, depending on the price of copper and cobalt. The divestiture will take FCX well above the $3 billion mark for the springing collateral clause mentioned in its annual filings.

We are a copper miner

“This transaction is another significant step to strengthen our balance sheet and enhance value for shareholders,” said Adkerson in the company’s press release. “Since the start of 2016, we have announced over $4 billion in asset sale transactions. We are committed to our immediate objective of reducing debt while retaining a large portfolio of high quality assets and resources and a leading position in the global copper industry.”

The future of Freeport-McMoRan’s oil and gas assets

What will become of FCX’s assets is difficult to say, especially in light of the current oil and gas commodity market, but it appears that Freeport’s management is ready to exit the oil and gas business and get back to mining. The majority of the company’s debt has come from its purchase of the assets, and its exposure to oil prices, something Freeport-McMoRan seems eager to change.

The company initially asked for $3 billion for its oil and gas arm, but the bid/ask spread is a chasm. Is Jim Flores a buyer as rumored? Does it matter? Regardless, the combined PXP and MMR assets had a PV-10 value of $14.1 billion. At the time of the combination, crude oil averaged $88.25 per barrel and natural gas was $3.44 per MMBTU.

Whether it was due to the bonding costs on the Gulf assets, or something else, the value of the assets declined substantially along with the price of oil, as the company’s 10-K filings illustrate.

In 2013, Freeport-McMoRan reported a PV-10 value of its oil and gas assets of $12.6 billion. The PV-10 value fell 36% to $8.14 billion in the company’s 2014 10-K, even as the SEC oil price deck remained above $90 per barrel. The value of FCX’s assets plunged another 83% year-over-year to just $1.4 billion at year-end 2015, according to the company’s most recent 10-K filing.

Multiple sources who spoke to Oil & Gas 360® were also unsure who might purchase the assets, but they believe a sale is expected in the next six to twelve months.

Whether a Flores-led team will make the purchases through a new entity, or if someone else comes forward to buy the assets is uncertain. But FCX looks primed to sell as it searches for to return to a pure play mining company.