Despite having shale-gas deposits to rival those in Appalachia, which made the U.S. a major exporter, Argentina’s domestic gas production sector has suffered from years of underinvestment that has left it unable to meet domestic demand, never mind the needs of the export market.

As a result, Argentina is competing for shipments of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, along with industrial powerhouses like the U.K. and Japan. Its timing could scarcely be worse, as prices have skyrocketed. The fallout from Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has plunged energy and commodity markets into chaos, worsening the shortages, supply-chain bottlenecks and wild price swings that have roiled the world economy since the pandemic emerged.

Furthermore, Argentina is only just starting to ask traders for cargoes for May and June, when winter in the southern hemisphere sets in. With the spike in prices over the last few weeks, the country — which has perennial shortages of hard currency used to pay for imports — may not be able to afford all the LNG it needs.

“Argentina was planning to import 60 to 65 LNG shiploads, but these prices force it to adjust that original strategy,” Marcos Bulgheroni, chief executive officer of Pan American Energy, one of the country’s biggest gas drillers, said at an oil conference last week in Buenos Aires.

To many observers, including people in the government and the gas-processing industry who asked not to be named because the matter is politically sensitive, the specter of fewer-than-needed LNG cargoes puts the country on the cusp of having to limit energy supplies to industrial consumers.

“It’s going to be a tough winter ahead for fuel supplies with the way access to hard currency is in Argentina,” Agustin Gerez, head of state energy company Ieasa, which arranges the country’s LNG tenders, said in an interview. He harbors hope of a mild winter that would curb demand.

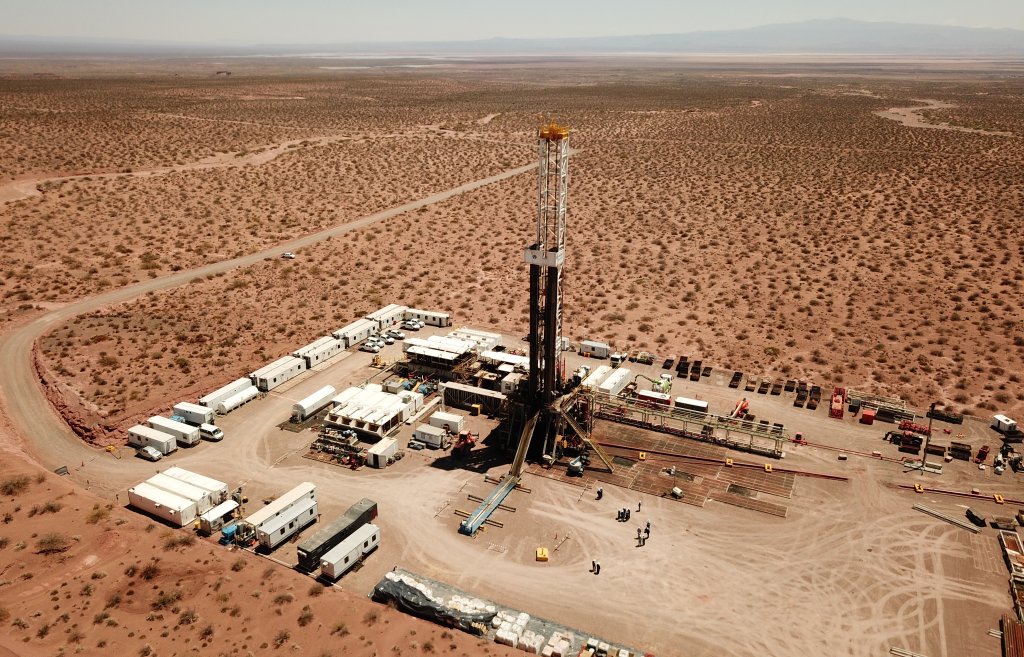

Much of the nation’s predicament was long in the making. A chronically poor business climate failed to lure enough spending in its Vaca Muerta shale patch and delayed the construction of pipelines needed to bring gas from the remote Patagonia region to industrial hubs and urban centers. Instead of becoming the shale powerhouse it had hoped to be, Argentina has become a major importer of LNG, mostly on the volatile global spot market, with the U.S. and Qatar as its top suppliers, shipping data compiled by Bloomberg show.

To make matters worse, negotiations to bring in more gas from neighboring Bolivia by pipeline have stumbled, and Argentina faces competition for those supplies, too, with Brazil taking the lion’s share. Argentina signed a 20-year gas deal with Bolivia back in 2006, before Vaca Muerta was even on the radar, but volumes and pricing are regularly renegotiated and the two countries have been locked in talks for months about supplies for the upcoming winter.

Argentina currently imports 7.5 million cubic meters a day from Bolivia, but needs roughly double that in the cold stretch from May to September. It’s unclear whether a deal on that scale can be reached when Bolivia’s supplies are dwindling, said Alvaro Rios, a former Bolivian oil and gas minister who now runs consultancy Gas Energy Latin America. Bolivia’s production has fallen 17% in the past four years as investments there slowed in the wake of gas field nationalizations.

“Argentina will need to rely more on LNG this year than last year,” said Henrique Anjos, an LNG analyst at global energy research firm Wood Mackenzie. “Bolivian production has been declining steeply and they have been prioritizing flows to Brazil.”

Other large economies in South America are better placed to withstand the soaring cost of natural gas, Anjos said. Chile has locked in long-term prices. In Brazil and Colombia, rainfall has picked up, boosting output from hydroelectric dams, while Argentina’s hydro power is still feeling the effects of a drought, putting pressure on its gas- and diesel-fueled power plants.

A silver lining for the country is that inflows from other dollar-denominated commodities that Argentina exports, such as soybeans, could somewhat offset the blow from importing LNG and diesel. Another helping hand comes from a pricing program for drillers.

“Without that we’d be in a much deeper hole,” said Juan Jose Carbajales, an energy professor who was the architect of the program as oil and gas secretary. “And with Argentina’s resources, we can only bounce back.”

Argentina could be self-sufficient in natural gas again and even become an LNG exporter, but it needs more pipelines. The first 430-mile stretch of a new trunk line isn’t expected to be completed until next year because the sputtering economy has constrained infrastructure investments and left companies locked out of credit markets.

The government has therefore stepped in to build the pipeline itself with tax revenues. When ready, it’ll “absolutely transform” Argentina’s energy industry, Ieasa’s Gerez said, allowing shale producers to ramp up investments and reduce the country’s reliance on imports. But oil executives say the pipeline needs to be accompanied by a broader policy mix that helps rather than hinders drillers, something that, if Argentine history is any guide, is no sure thing.

“Argentina has to take the decision,” Alberto Saggese, CEO of Gas y Petroleo del Neuquen SA, the provincial-run driller in Vaca Muerta, said at a conference last week. “Do we want to be an exporter or do we want to leave all that gas underground?”