The setting for 2021 seems clear: A powerful growth trajectory fueled by an influx of government spending as the U.S. recovers from the Covid-19 crisis and heads into the fastest economic acceleration in nearly 40 years.

But after that, then what?

The path beyond this rocket-fueled year looks far less clear.

One-time spending has rarely been the catalyst for long-term growth. Fiscal and monetary policy that now serve as irresistible tailwinds could soon turn into headwinds. On the other side of this huge burst of activity will be an economy beset by inequality and a two-speed recovery that likely will take more than the occasional government transfer payment.

So while gross domestic product growth in 2021 could reach 7% or beyond, don’t get used to it. An economic reckoning is likely ahead.

“I don’t see growth as being particularly durable,” said Joseph LaVorgna, chief economist for the Americas at Natixis. “The economy is going to slow a lot more next year than people think and probably will be well under 3%.”

LaVorgna, the chief economist of former President Donald Trump’s National Economic Council, sees a number of obstacles, many of them related to policy.

In the immediate climate, trillions in direct payments have helped buoy consumer spending and imports. But the trend so far has been for robust credit and debit card spending to cool off once the initial jolt from the stimulus checks ebbs.

Looming ahead are higher tax rates for corporations and wealthier Americans. Also, the Biden administration’s intense focus on addressing climate issues likely will add to the regulatory burden that is particularly tough on smaller businesses.

“How 2022 unfolds with respect to Congress is going to be a significant inhibitor to long-term business planning and decision-making, at least to the extent that you’re not going to get a robust set of capital expenditure plans in place,” LaVorgna said.

“At this point, I don’t see [businesses] making a big longer-term commitment either to factory build-outs or anything that would have a long shelf life, because you’re not sure what the regulatory and tax environment looks like.”

Then there’s the issue of those on the bottom rungs of the economic ladder.

While the transfer payments help in the short run, employment data continues to indicate a slow recovery for lower earners, with stubbornly high weekly jobless claims and a gap remaining of 3 million hospitality jobs that appear a long way from coming back. Federal Reserve estimates still have the jobless rate for the bottom quintile in the 20% range.

“Everyone’s expecting a turn-key economy: We just need to reopen and move on and things will go perfectly,” said Nela Richardson, chief economist at payroll processing firm ADP, which circulates a widely followed monthly count of private payroll jobs. “I don’t think you’ll get turn-key. There’s been significant scarring in the labor market. There’s been damage done to some consumers.”

Richardson is in the camp of those seeing a K-shaped recovery, where those on the higher rungs have maintained or even thrived during the pandemic, while those at the bottom have lost ground.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said in an interview that aired Sunday on CBS’ “60 Minutes” that the central bank is attuned to the issues confronting service industry workers and pledged to keep the policy focus in that direction.

“It’s going to take some time. The good news is that we’re starting to make progress now. The numbers show that people are returning to restaurants now,” Powell said. “But I think we need to keep in mind, we’re not going to forget those people who were left on the beach really without jobs as this expansion continues. We’re going to continue to support the economy until recovery is really complete.”

Fed policy risk

That policy support has been critical in both getting the economy going again and keeping financial markets functioning.

Fed officials believe they can continue to press the accelerator to the floor without risking a troublesome rise in inflation, even as consumer prices rose 2.6% in March from the year before and 0.6% from the previous month.

Powell and his fellow policymakers see the recent inflation trends as temporary and the result of supply chain issues that will dissipate, along with easy comparisons to a year ago when inflation vanished as the pandemic hit.

But the Fed, and particularly the Powell Fed, has run into trouble before when trying to forecast over long ranges.

In late 2018, the central bank had to backpedal from plans to continue raising rates when issues relating to the trade war hit the global economy. A little over a year later, the Fed’s pledge to stop cutting rates went away when the pandemic hit.

While defenders of the Fed might say that those were unforeseen events, that’s the point: Making long-term policy pledges is a Sisyphean task in a global economy where the sands shift so frequently.

“The biggest risk to the expansion is the Fed,” said Steve Blitz, chief U.S. economist at TS Lombard. “The puppet master is trying to control a puppet that they do not have control over.”

Still, Blitz thinks the Fed’s policy pivot last year, in which it has pledged not to tighten until it sees actual inflation rather than just forecasts is “the right thing, because their forecasts stink.”

Both monetary policy from the Fed and fiscal policy from Congress overall is likely to stay loose until the economy’s underlying issues are addressed, he added.

“Everybody recognizes the political costs of ignoring the middle now are too high,” Blitz said. “Both parties are sitting on the knife’s edge. Who can do the best through fiscal spending … at winning back that middle vote?”

Consumers are spending and saving

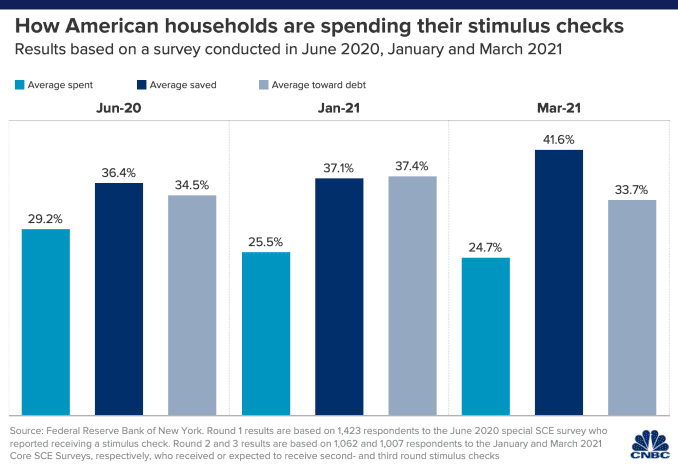

Consumers so far are using some of the stimulus they’ve received from Congress both to buy and invest, yet continue to show caution.

The three rounds of checks have seen progressively less spent and more saved, according to New York Fed data. The numbers tell a twin message—that consumers are building up their balance sheets, indicating large spending power ahead, but also are growing increasingly reluctant to part with that cash.

What economists call the marginal propensity to consume has fallen from 29% in the first round of stimulus checks in the spring of 2020 to 25% in the most recent distribution.

“As the economy reopens and fear and uncertainty recede, the high levels of saving should facilitate more spending in the future,” New York Fed economists said in a recent report. “However, a great deal of uncertainty and discussion exists about the pace of this spending increase and the extent of pent-up demand.”

Indeed, the future of the economy beyond the stimulus-fueled breakout of 2021 will depend largely on that story of how much folks really can’t wait to spend after being holed up for a year, and how long that will last.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, is more optimistic about the economy’s fate. He looks to yet another burst of activity coming from the looming infrastructure bill, with spending that likely won’t take root until 2023 and beyond.

“This will jumpstart a self-sustaining economic expansion. There’s so much juice here that we’re going to get back to full employment in the next 18 to 24 months,” Zandi said. “Once this near-term juice winds down, we’re going to get another shot.”

The economy will have much to weather in that period, though.

As always, there’s the pandemic. While almost all of the news with vaccines has been good, a sudden spike in variants could cause some jittery elected officials to lock down portions of the economy again.

And there’s the inflation question.

If the Fed has it right, it can keep policy loose and growth can continue. If it gets it wrong, Powell has conceded that the primary tool will be interest rate hikes that, while unlikely to snuff out the recovery, could significantly slow it. Housing, which has led the economy out of the recovery, would take the biggest hit.

St. Louis Fed economist Fernando Martin said a combination of rising inflation expectations, falling unemployment and the surge in money supply to the economy could apply longer-lasting inflation than policymakers currently suggest.

“If these pressures materialize and prove persistent, the Fed will have to eventually step in to lower inflation and achieve its goal of 2% average inflation,” Martin wrote, though he also said it’s possible inflation could stay low.

There’s also likely to be a fiscal reckoning.

Halfway through the fiscal year, the government already is running a $1.7 trillion budget deficit as the total national debt recently passed the $28 trillion level. The public share of that debt is about $22 trillion, or 102% of GDP.

Congress heading into midterm elections next year may want to look more fiscally responsible and thus choke off the free-wheeling spending that will fuel the economy this year to likely its strongest annual performance since 1984.

Zandi sees a policy shift as perhaps the greatest danger to the longer-run economic view.

“For the economy not to engage in a self-sustaining expansion will take a policy error,” he said. “We’ll have to do something wrong. Either the Fed brakes too hard or fiscal policymakers don’t pass more support.”

That support is essential as the country tries to avoid a recovery that leaves too many behind, Zandi added.

“The risks are considerable. It goes to a K-shaped recovery, income and wealth inequality, racial inequality issues, climate change,” he said. “These are deep-seated problems that I don’t think can be addressed without a very fulsome policy response.”