U.S. energy companies are taking an axe to their rig numbers, deepening production cuts for the industry that in the last few years made America the world’s number one oil producer.

Six major U.S. shale producers are expected to shut some 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude for the months of May and June, according to an analysis of the companies’ early communication by Rystad Energy.

“Analyzing communication by Continental Resources, Cimarex Energy, ConocoPhillips, PDC Energy, Parsley Energy and Enerplus Corporation, we estimate that oil production cuts in May and June 2020 could amount to 300,000 bpd, an increase from about 100,000 bpd of cuts projected for April 2020,” Rystad wrote in a report Tuesday.

In March, American producers were still pumping at record highs, according to the Energy Information Administration, even as prices plunged due to the loss of demand from the coronavirus pandemic. The latest weekly government data shows production at 12.2 million bpd in the third week of April, the lowest level since July and a stunning 900,000 bpd less than its record peak of 13.1 million bpd in early March.

Oklahoma-based Continental Resources is taking “the most drastic action thus far,” Rystad reported, forecasting a drop of 69,000 bpd from Continental in April and a cut of nearly 150,000 bpd in May and June. Houston, Texas-based ConocoPhillips has announced some 125,000 barrels of oil equivalent of gross output to be slashed in May, Rystad wrote, “estimated to amount to around 60,000 bpd of oil net to the company.”

Artem Abramov, Rystad’s head of shale research, estimates a further production decline of “900,000 bpd, 250,000 bpd and 400,000 bpd in Permian, Eagle Ford and Bakken throughout 2Q20 respectively,” referring to the biggest shale formations in the U.S., with shut-ins accounting for 60% of that initially.

As rigs disappear, US is set to return to ‘net importer’ status

When OPEC and non-OPEC producer countries including Russia, Canada, Norway and Brazil joined forces to implement a coordinated oil production cut to put a floor under prices — by a historic 9.7 million bpd from May 1 — the U.S. did not technically join, relying instead on market dynamics to force production down. That’s happening now, both in the form of companies shutting in their wells and cutting investment and projects for new wells.

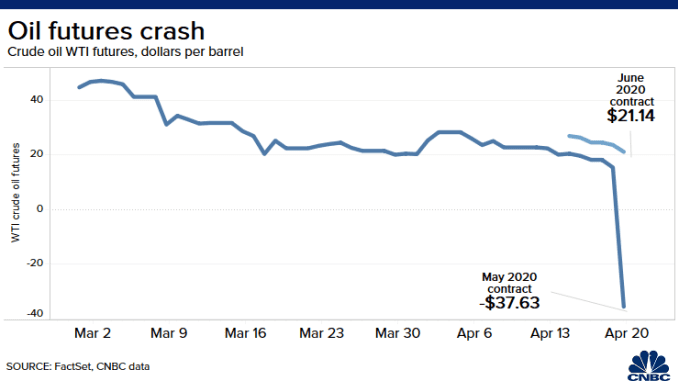

The industry hit its most glaring crisis point on April 20 when for the first time in history the price of oil dove below zero, and the May futures contract for U.S. oil benchmark West Texas Intermediate hit negative $40 per barrel as storage space disappeared and producers were literally paying buyers to take the oil off their hands. WTI’s price is currently down more than 75% year-to-date.

Energy analysts are warning of a repeat meltdown for WTI’s June futures contract, as storage space is expected to run out within weeks. With no certainty as to when demand will return and lockdowns will subside, the EIA expects U.S. oil output to be down to 11 million bpd by 2021. S&P Global Platts predicted in early April a more than 50% fall in rigs with proportional job losses.

And with production costs much higher than most of its global competitors, the EIA actually expects the U.S. to “return to being a net importer of crude oil and

petroleum products in the third quarter of 2020.”

Exxon is cutting its capital spending globally by 30%. In U.S. shale, the oil major recently had 58 rigs in operation in Texas’s shale-rich Permian basin — that number is likely to fall to 15, according to analysts at Houston-based investment bank Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. Exxon CEO Darren Woods expects oil demand to fall by between 25% and 30% in the immediate term.

‘We have all destroyed capital’

The energy sector is shrinking so dramatically that it’s become the second-smallest group in the whole S&P index. The industry now represents just 3% of the index, compared to 15% a decade ago and 30% in 1980.

Market watchers are now questioning whether the U.S. shale industry — fuelled for years by cheap money and drowning in debt — will ever be able to attract investors again, save for the large-cap companies whose balance sheets will allow them to survive this downturn.

As Andrew Logan, senior director of oil and gas at Ceres, asked in a recent CNBC op-ed: “Why would an investor risk capital in an industry saddled with debt where the main product can go below breakeven costs for long periods of time?”

Pioneer Resources CEO Scott Sheffield echoed that sentiment earlier this month, admitting during a meeting with the Texas Railroad Commission that: “No one wants to give us capital because we have all destroyed capital and created economic waste.”

[contextly_sidebar id=”SHUTbXy0ra7Jv0Yr8lFYuegjMnbSiW6l”]