Study looks at effects of shipping U.S. LNG using U.S.-built ships

Cheniere Energy (ticker: LNG) is expected to begin shipping 3.5 Bcf/d of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from its Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana early next year, with an additional 6.27 Bcf/d of capacity expected to come online in the U.S. before 2019.

The increased capacity will turn the U.S. into a net exporter, requiring more than 100 more LNG carriers to ship the LNG to customers around the world, according to new research from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

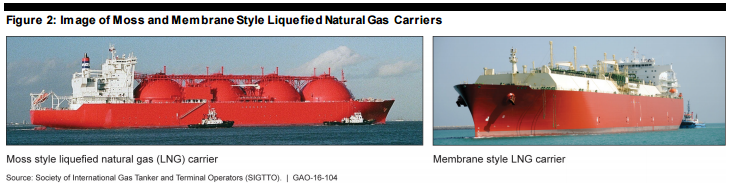

The GAO’s study also explored what it would mean for the U.S. economy if LNG exported from the U.S. was also shipped using LNG carriers built here in the United States. Currently operating LNG carriers are nearly all foreign-built and operated, with no carriers operating under the U.S. flag. Constructing LNG carriers here in the U.S. would likely create jobs, says the GAO, but might also hurt demand for U.S. LNG.

To spur jobs growth, Congress may require U.S. LNG to be shipped on U.S.-built carriers under the U.S. flag; but would the ensuing 30-year backlog to build the required capacity kill the LNG export boom?

Congress is considering legislation that would require all LNG exported from the U.S. to be transported by carriers built in the U.S., and operated under its flag. The legislation is designed to increase jobs in both the shipbuilding and maritime industries, according to the GAO.

Requiring U.S.-produced LNG to be shipped by tankers made here in the U.S. would create 4,000-5,200 maritime jobs in order to meet the manpower necessary for the 100 vessels, according to the GAO, but only if the new law does not affect the demand for U.S. LNG.

U.S. shipbuilding capability is extremely limited

Unfortunately, this is where the legislation could run into problems, says the GAO. Only two shipyards contacted by the group currently possess docks long enough to construct an LNG carrier, and both reported that they currently have vessel orders that take up their shipbuilding capacity through approximately 2018. Because the two shipyards are already booked, it will be some time before construction can begin without “substantial capital improvements” made to other shipyards in order to construct docks long enough to build the carriers.

Once space has been secured to construct the new vessel, it would take about four to five years to build a carrier from time of initial contact with a buyer, says the GAO, putting the ships well behind the development of U.S. liquefaction capacity. Based on the productivity rates quoted to the GAO by shipbuilders, it would then take about 30 years to build the 100-carrier fleet potentially needed to meet U.S. export capacity.

Can U.S. shipbuilders with capacity of 1-2 ships per year compete with Asian shipbuilders whose shipbuilding capacity is 50-80 ships per year?

Part of the reason for the long development of an all U.S.-made fleet is a lack of experience in U.S. shipyards, says the GAO. Compared to the one or two vessels per year a U.S. shipbuilder might be able to make, Asian shipyards are capable of delivering 50-80 large ships per year.

“As a result of U.S. shipyards’ capacity constraints, as well as their anticipated lower productivity than foreign shipyards, LNG carriers built in U.S. shipyards would likely cost more than those currently built in foreign shipyards,” wrote the GAO. While no U.S. shipyard currently builds LNG carriers, making an exact price difficult to determine, the GAO estimates that a U.S.-built LNG carrier would likely cost $400-$675 million, or two to three times as expensive as the $200-$225 million required to build an LNG carrier overseas.

Another ‘Jones Act’?

“Generally, the Jones Act [federal statute 46 USC section 883 in maritime law] prohibits any foreign built or foreign flagged vessel from engaging in coastwise trade within the United States,” according to the Maritime Law Center’s website. But if Congress enacts a new law that restricts shipping of U.S.-produced LNG to U.S.-built and flagged ships, the effect is like putting another ‘Jones Act’ in place—but this version would restrict the delivery of U.S. energy to foreign customers at a time when exporting U.S. energy is critical to Asian and European customers. It is also critical to the nascent LNG export operations like Cheniere’s Sabine Pass and others that are in various stages of planning, design and construction in the U.S., and to the U.S. natural gas producers who are looking to diversify their customer bases at a time when natural gas is gaining ground as a reduced-carbon fuel for electricity generation in developed nations.

Requiring U.S. LNG carriers may kill the competitive advantage of U.S. LNG

While the construction of a 100-ship fleet would add more jobs into the U.S. economy, it would likely add to the cost of U.S. LNG exports, making them less competitive in global markets.

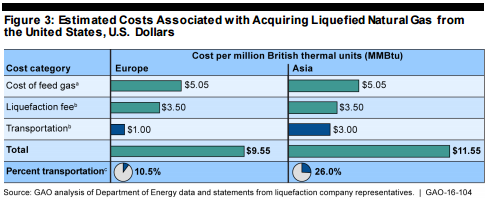

According to the GAO, an LNG fleet operated under U.S. flags would be 50% more expensive. This, combined with the more expensive build costs, would increase shipping costs by about 24%, or $0.73 per MMBtu.

Because transportation makes up more than a quarter of the cost to Asian markets, the increased shipping costs would likely lower demand for U.S. LNG. While the exact extent of the reduced demand is unclear, “any reduction in demand for U.S. exports due to the proposed requirements and resulting changes to the LNG market may decrease jobs in other U.S. industries such as the liquefaction and the oil and gas industries,” said the GAO.

Adding to the uncertainty around the effects of the legislation on U.S. LNG, changing the laws around exports of U.S. LNG could cause contractual problems. LNG buyers might invoke force majeure or impracticability clauses in their contracts in order to modify, renegotiate or terminate the deals. Because most of the liquefaction capacity preparing to come online is tied to long-term contracts, this could prove problematic for the companies preparing to export LNG.

While the legislation would likely create welcomed jobs for U.S. shipbuilders and sailors, the increased costs and expanded timeframe required for LNG exporters to adhere to the legislation would also reduce demand for U.S. LNG. Lower demand could mean fewer ships required, and ultimately less need for the jobs the legislation was meant to create.