From Petroleum Planet/Alaska Journal of Commerce

Russia started as a bit player on the liquefied natural gas stage less than a decade ago but is not content in that role and wants to share top billing.

In 2009, when Russia’s first LNG export terminal went online, the Sakhalin-2 project in the Far East provided about 4 percent of the world’s liquefaction capacity. When the country’s second liquefaction plant, Yamal LNG, reaches full capacity early next year, Russia will have moved up to 26 million tonnes annual capacity, 7 percent of the world’s total.

If gas producer Novatek, which operates Yamal LNG, goes ahead with its plan for a second project in the Siberian Arctic, Russia could climb to 46 million tonnes in the 2020s, in the No. 4 spot behind Qatar, Australia and the United States.

Plans to expand Sakhalin production would further bolster Russia’s position in Asian markets, where it holds a decided geographic advantage. The Sakhalin terminal is just 750 miles north of Tokyo

Novatek’s own long-term goal is to produce 55 million to 60 million tonnes of LNG per year by 2030, company CEO Leonid Mikhelson said earlier this month.

Government financing, tax breaks, building infrastructure and providing icebreakers are part of the plan.

“Don’t think of these as commercial projects,” a global energy analyst foretold at a Washington, D.C., conference six years ago.

Rather, he said, accept that Russian politics are part of the equation. The government might be willing to subsidize a project to promote economic development or to gain momentum in the growing Asian market.

That same summer as the Washington conference, Russian President Vladimir Putin signaled the gradual end of state-controlled Gazprom’s monopoly on gas exports, opening the way for rivals, including Novatek, to do business in Asia. Gazprom has long profited from its exclusive position in pipeline gas sales to Europe, which Putin did not touch. The easing of export restrictions applied only to LNG.

As part of the decision to promote LNG exports, the government’s 2013 actions included reducing its mineral extraction tax and canceling export duties on new Arctic offshore oil and gas projects.

The government further assisted in Yamal by financing construction of a port, airport, pipelines, icebreakers and dredging to create a navigable channel to the port, at a cost of at least $9 billion. The regional government contributed a property tax exemption and lower corporate profits tax rate.

Just five years later, two of three liquefaction trains are now in production at Yamal, with the third train scheduled to start up early 2019, bringing the $27 billion project’s capacity to 16.5 million tonnes per year. The partners are Novatek (50.1 percent), France’s Total (20 percent), China National Petroleum Corp. (20 percent) and China’s Silk Road Fund (9.9 percent).

China also provided $12 billion in financing for Yamal, after U.S. sanctions blocked other lenders.

Novatek and the country’s top oil producer, Rosneft, both lobbied for LNG export rights. Rosneft and its partner ExxonMobil for years have considered adding a gas liquefaction plant to their Sakhalin-1 project, which started producing oil in 2005. Though the companies continue to plan their own LNG plant, Gazprom would prefer that they pay to run their gas through its Sakhalin-2 project.

Reuters this spring reported that ExxonMobil and Rosneft had invited companies, including China National Petroleum Corp.’s engineering arm, to submit construction bids by October for their $15 billion LNG project with an initial capacity of 6 million tonnes per year. The news service reported a final investment decision is due next year.

Gazprom, meanwhile, is looking at adding a third train at its Sakhalin plant but lacks enough gas reserves for the expansion. Reaching a deal with ExxonMobil/Rosneft for supply would be the fastest option using existing infrastructure because some of the gas is being pumped back into reservoirs, Sakhalin-2 commercial director Andrey Okhotkin told a Russian LNG conference this summer.

While oil and gas giants Gazprom and Rosneft are active in the Far East, Novatek wants to expand in the Arctic. The company is targeting mid-2019 for a final investment decision on its Arctic LNG-2 plant, which would be built east of Yamal. Estimated at $25.5 billion, the plant is proposed at 19.8 million tonnes per year, with start-up in 2022-23.

In June, Total agreed to buy a 10 percent stake in the venture, and Novatek has signed a memorandum of understanding with Korea Gas expressing “mutual interest for KOGAS to enter into the Arctic LNG-2 project.” Talks also are underway with Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, China National Petroleum Co. and Japan’s Marubeni Corp.

In anticipation of going ahead with Arctic LNG-2, Novatek is building a shipyard in the port city of Murmansk for construction of the production modules that would be towed to the plant site on the Gydan Peninsula.

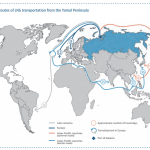

Ice-class LNG carriers move Yamal gas through the Northern Sea Route to East Asia and also westward to Europe, but the ships are significantly more expensive to build and operate than the usual LNG tankers. Novatek is pursuing an answer to that costly dilemma — trans-shipment terminals to transfer the fuel to less-expensive, traditional carriers after the ice-class ships have reached open water.

The company wants to build an LNG trans-shipment terminal by 2023 on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, about 1,500 miles north of Tokyo. Trading house Marubeni and shipbuilder Mitsui O.S.K. Lines are among the Japanese companies considering participation in the project.

Tokyo also might help through public institutions such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance, according to a report in the Nikkei Asian Review.

And if one trans-shipment terminal is good, two might be better. Novatek is considering building an LNG trans-shipment terminal near Murmansk, CEO Mikhelson said Aug. 20.

The location will be determined “in the nearest future,” Mikhelson said. The use of Ura Bay, 25 miles from Murmansk, is under discussion with Russia’s Defense Ministry, which operates a submarine base nearby. The transfer terminal, on the route from Yamal to Europe, would strengthen the company’s positions in the global LNG market, Mikhelson said.

“We are losing,” he said, “and will continue losing in transportation with ice-breaking tankers.”