P5+1 used financial isolation to force Iran to nuclear negotiation table

A sanctions regime was put in place against Iran starting in 2005 when the international community found that the Middle Eastern country was not in compliance with its obligations regarding its nuclear program. The sanctions, which were spearheaded by the United States, United Nations and the European Union, sought to financially isolate Iran in order to bring it to the negotiation table with the international community.

Sanctions against Iran vary from asset freezes, to preventing foreign-based financial institutions or subsidiaries that deal with sanctioned banks from conducting deals in the U.S. or with the U.S. dollar, which then-Treasury Under Secretary David Cohen called “a death penalty for any international bank,” according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

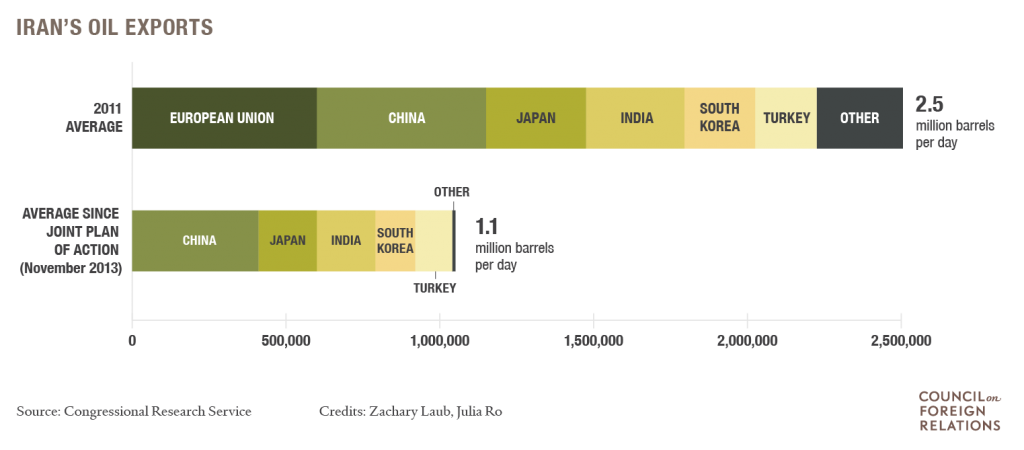

As part of a 2013 initiative, called the Joint Plan of Action (JPA), the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council and Germany (P5+1) agreed to also cap Iran’s crude oil exports at 1.1 million barrels per day (MMBOPD).

The combined sanctions regimes put enough pressure on Iran that the country decided to negotiate with the P5+1, and on July 14, 2015, an initial deal was finalized. Under the deal, the international community has agreed to lift some of the sanctions in exchange for compliance with international standards on Iran’s nuclear program.

The Iran deal sends shocks through the commodities market

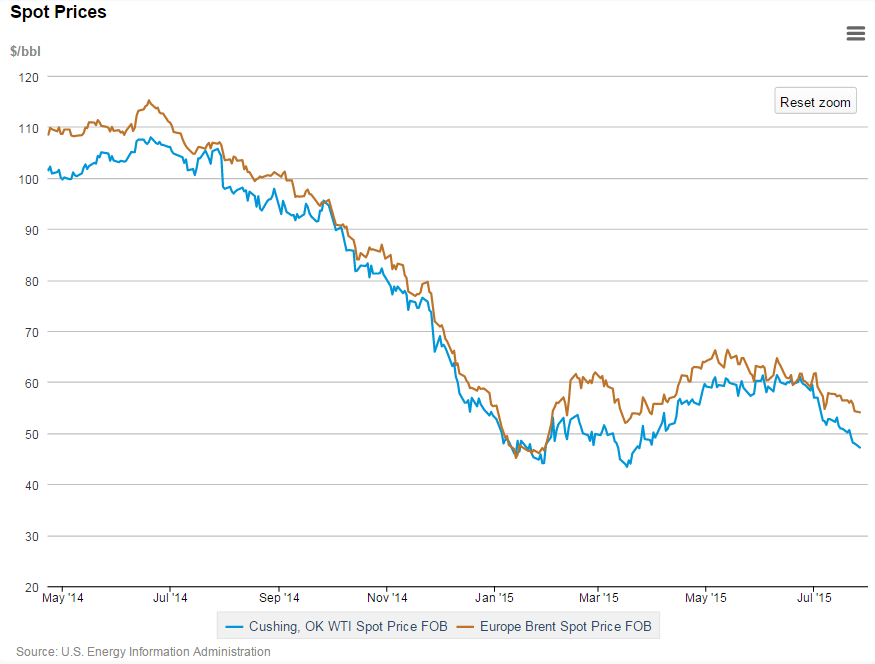

The U.S. crude oil benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), saw its largest single-day drop in price on concerns of Iran adding to an already oversupplied market, in addition to the Greek financial crisis and weakness in the Chinese stock market, on July 6. WTI shed 7.5% of its value after slowly pushing its way up from $43 per barrel in the middle of March, to around $61 per barrel on June 10.

While the chances of such a dramatic single-day drop in WTI prices were 1 in 2,000 according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), it remained the largest single-day drop in the U.S. benchmark crude’s price since February 4, when WTI fell 8.5% when inventories built over 6,000 MBO and demand decreased by 10%, sending WTI prices below the $50 threshold.

A report from SVB Energy International said that increased Iranian exports would cause “more of a psychological impact on the market and the prices, rather than an actual effect.” The uncertainty around how much supply might actually come out of Iran, and when, has continued to push prices down. On July 22, WTI closed the day at $49.19, the first time it had finished the day below $50 since April 2, 2015.

Uncertainty persists

Experts differ widely on what they believe Iran’s oil and gas sector is capable of, though everyone agrees more oil added to an already oversupplied market will have a negative impact on prices. SVB expects that the country will add as much as 800 MBOPD (400-600 MBOPD in crude and an additional 200 MBOPD in condensate) in the next 6-12 months, while others, like Wood Mackenzie, think that it will be year-end 2017 before Iran adds an additional 600 MBOPD to its production.

Iran’s production goal = 5 MMBOPD; but needs $280 billion in foreign investment to revitalize sector

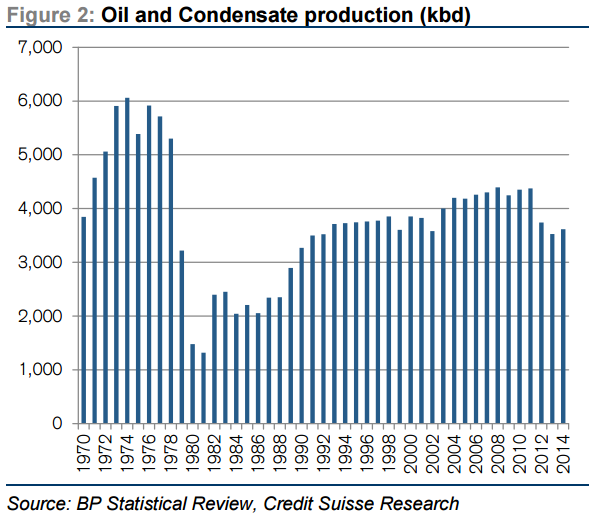

Iran’s goal is to reach 5 MMBOPD by 2020, about 1 MMBOPD more than the country produced before the crude oil sanctions were put in place. Iran’s oil minister, Bijan Zanganeh, believes that Iran will require $20 billion of investment into its industry in order to reach that goal, and hopes to raise $280 billion to completely revitalize its oil and gas sector.

Dr. Iman Nasseri of FGE, an international energy consulting group, spoke with Oil & Gas 360® to explain FGE’s perspective on Iranian exports, and what the deal could mean for the country as a whole. Dr. Nasseri has his PhD in Economics, focusing on energy and environments, from the University of Hawaii. Before joining FGE, he worked for Iran’s Institute of International Energy Studies, the research arm of the Ministry of Petroleum.

“A lot of people have been saying Iran has lost its potential, and that it takes years to turn it back on, but they haven’t actually been to Iran,” said Nasseri. “We’ve been talking with the current administration, and they are telling us that they have been maintaining fields in the past two years and the fields are ready to increase production by about 500 MBOPD, and then they can ramp up to an additional 1 MMBOPD, which is basically pre-sanctions levels.” Nasseri went on to explain that FGE predicts that Iran will reach pre-sanctions levels of 4.0-4.2 MMBOPD by mid-2016.

There is more to the P5+1 deal with Iran than just oil, however, and sanctions are not expected to come off immediately. During a Wells Fargo conference call, Reuel Marc Gerecht, a senior fellow with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said that it could be some time before the IAEA certifies that Iran is in compliance with the nuclear portion of the deal. “The IAEA might be the only wrench in this,” he explained. “The [Obama] administration wants the deal certified within 60 days, but some of the testing required could take six months.”

Gerecht went on to say that the deal is more complicated on the Iranian side than some people realize. Not everyone in Iran likes the deal, said Gercht, and different factions within the Iranian government need to be satisfied before the deal can go ahead. “Think of them as competing mafias vying for the oil wealth,” said Gerecht.

Iran stands to gain more than oil revenue if sanctions are lifted, explained Nasseri. “Iran’s economy was hurt a lot worse than just the lost oil revenue. Once sanctions are lifted, it will mean a revitalization of the entire industrial sector. Iran is looking forward to exports, but it’s bigger than that too,” said Nasseri. After sanctions were put in place, Iran’s currency, the rial, lost two-thirds of its value, and the country lost access to technology and expertise required to further develop various industries.

Foreign investment a must

The timing on the lifting of sanctions is still uncertain, but once Iran does come back to the international market, it will still require international investment in order to reach its goal of 5 MMBOPD by 2020. Geopolitical Analysts for Energy Aspects Richard Mallinson said international oil companies (IOCs) are still uncertain about the investment climate. Mallinson believes that Iran will likely add 300-500 MBOPD of additional oil exports to the market, but not until after sanctions have been lifted, which he pegs at the beginning of 2016 at the earliest.

Iranian Petroleum Contracts: making Iran more attractive than Iraq, Brazil or the UAE

Much of the uncertainty for IOCs revolves around Iran’s new contracts. Because of conflicts with Iranian constitutional law, IOCs are not allowed to own the actual production coming out of the ground, meaning Iran does not offer the typical production-sharing style contract to IOCs.

Nasseri said that the group responsible for developing the new contracts has done its best to remedy this issue. “They cannot change the law, but what they have done with the new Iranian Petroleum Contracts (IPCs) is to take a service contract and make it function like a production sharing contract,” he said.

The final version of the new IPC will not be made available until the end of this year, but Nasseri said the draft versions he has seen so far are promising. “The developers of upstream resources will be paid a service fee per barrel of oil produced, but they have made that fee variable,” he explains. “The fee will change based on the amount of production, whether the project is offshore or onshore, and other factors will also contribute to determining how much the IOC will receive for its services.” By tying the contract to services provided by the IOC, rather than production coming out of the ground, the IPCs hope to attract investors without violating Iranian law.

The main goal in developing the new IPC was to make Iran a more attractive investment climate than other underdeveloped oil jurisdictions, said Nasseri. “The hope with the new IPCs was to make Iran more attractive than Iraq, Brazil or the United Arab Emirates,” he explained.

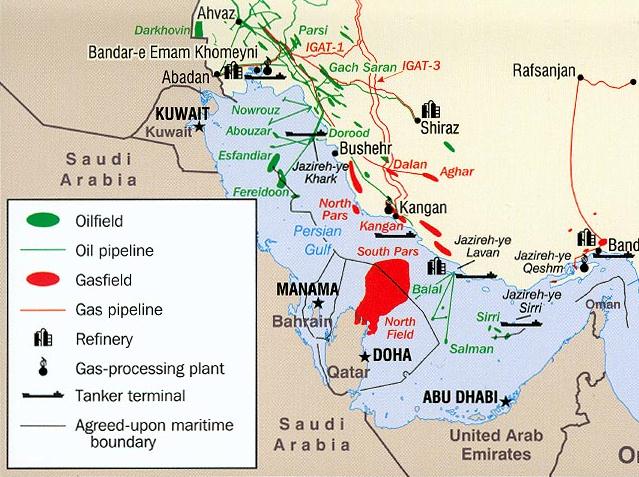

Natural gas development is top priority: 4+ Bcf/d could be exported from South Pars by 2021

Iran hopes to continue developing its natural gas industry as well as its oil. “Brining in investment for natural gas development is a top priority,” said Nasseri. Iran has massive natural gas reserves, especially in its South Pars field, but they have been left largely undeveloped.

“The future of natural gas development will be rapid,” explains Nasseri. “FGE’s expectations were, even without the lifting of sanctions, that development would be finished in about 10 years. With investment, it will be much faster. I believe we will see 7-8 Bcf/d from South Pars in the next 5-6 years.”

FGE believes that more than half of that could be sold as export, making Iran a major regional playing in natural gas in the Middle East.

Global chess game: Iran wants to export its oil but doesn’t want a price war

“Unfortunately, the timing for Iran’s oil coming back on the market couldn’t be worse,” said Nasseri. “The market is already 1-2 MMBOPD long, so how much of their added production Iran can actually sell is difficult to say. FGE believes that an additional 500 MBOPD is possible, but beyond that it will be difficult for Iran.”

Adding to the global supply glut will almost certainly put more downward pressure on oil prices. FGE predicts that it could send prices down an additional $5 to $10 per barrel. William Featherston at UBS predicts that Iran’s added crude could mean oil will not return to “midcycle prices” of $90/$85 Brent/WTI until 2018.

“Iran is going to face a dilemma,” said Nasseri. “They want to increase their exports, but they’re also not interested in a price war. They have already told OPEC that they plan to increase their exports, and they expect OPEC to make room for them in the market. It’s going to be a tough sell, but Iran wants to make it happen through diplomacy.”