A shot heard round the world

Last November 27, OPEC sparked the decline in crude oil prices that would see both international benchmark Brent crude, and U.S. benchmark WTI crude, lose more than 50% of their value. The group decided to move away from its traditional role of maintaining a reasonable crude oil price in order to protect its market share around the world in the face of higher production from hydraulic fracturing in the United States.

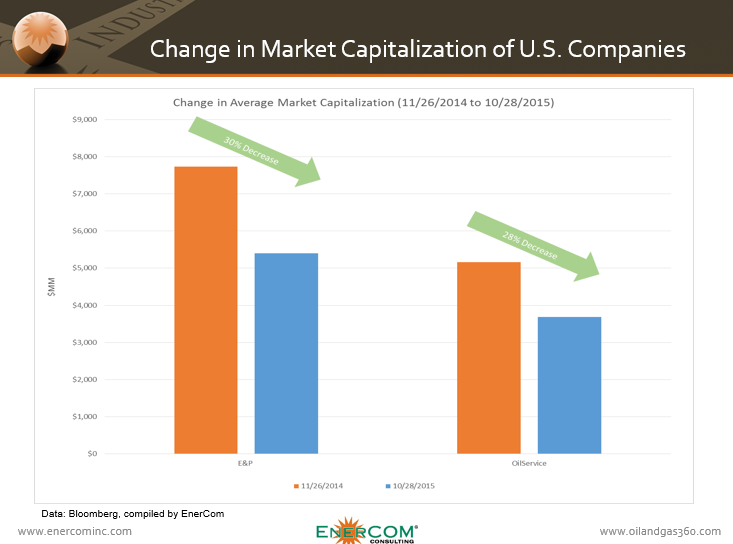

The OPEC decision, which the group finalized on Thanksgiving Day 2014, fundamentally changed the landscape of global oil markets. Producers were forced to focus on their most economic acreage and find ways to increase efficiencies in order to maximize their well economics. U.S. E&P companies in EnerCom’s E&P database saw their market capitalization decline by approximately 30% from November 26, 2014, the day before the OPEC decision, to the end of October, 2015. Over the same time period, companies in EnerCom’s Oilservice database saw their market capitalization decline by 28%.

OPEC hoped the decision would force higher-cost producers, like those behind the U.S. shale revolution, out of the market.

“We want to tell the world that high efficiency producing countries are the ones that deserve market share,” said Saudi Arabian Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi, shortly after the group’s decision. “If the price falls, it falls… Others will be harmed greatly before we feel any pain.”

The name of the game: efficiency

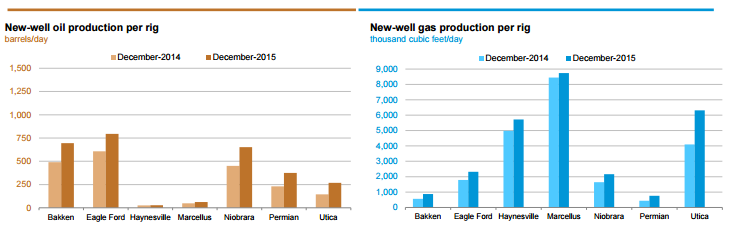

OPEC’s decision sent rig counts in the U.S. plummeting. The number of rigs actively drilling in the U.S. is down 61% as opposed to one year ago for the week ended November 20, 2015. Despite the significantly lower number of rigs drilling, production did not follow suit in the way Naimi predicted.

Operators targeted efficiencies, and production from new wells began to increase for all major oil and gas plays across the United States, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

U.S. shale production continued to climb for approximately six months following the OPEC Thanksgiving Day decision, before leveling off in June and returning to levels close to those seen at the end of November, 2014. U.S. oil production peaked in March at 9.7 MMBOPD, according to the Energy Information Administration, but declined to around 9.1 MMBOPD in September. Production at the end of November 2014 stood at 9.08 MMBOPD, according to data from Bloomberg.

Greater efficiencies and the energy revolution that followed the use of hydraulic fracturing has also led to record high U.S. natural gas reserves, according to the EIA. In 2014, U.S. crude oil and lease condensate proved reserves increased to 39.9 billion barrels – an increase of 3.4 billion barrels (9.3%) from 2013. U.S. proved reserves of crude oil and lease condensate have risen for six consecutive years, and exceeded 39 billion barrels for the first time since 1972.

Saudi Arabia continued to push rig counts higher

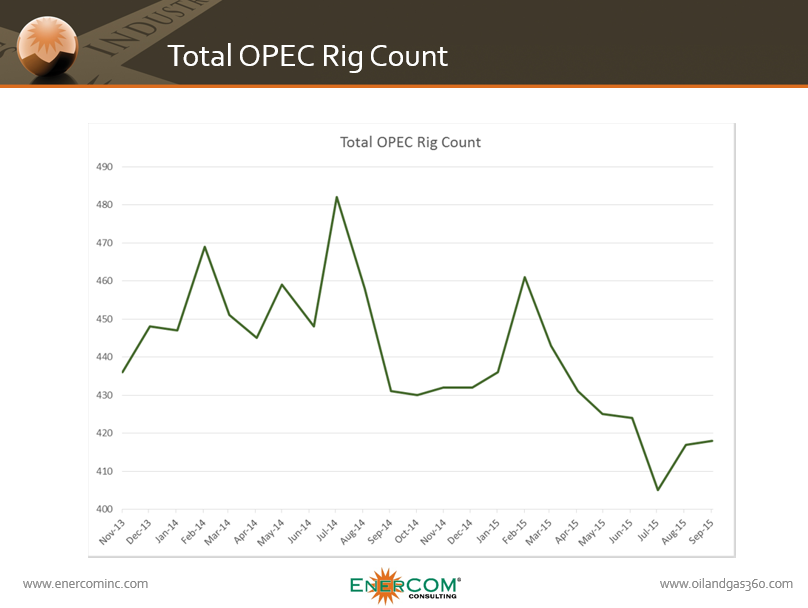

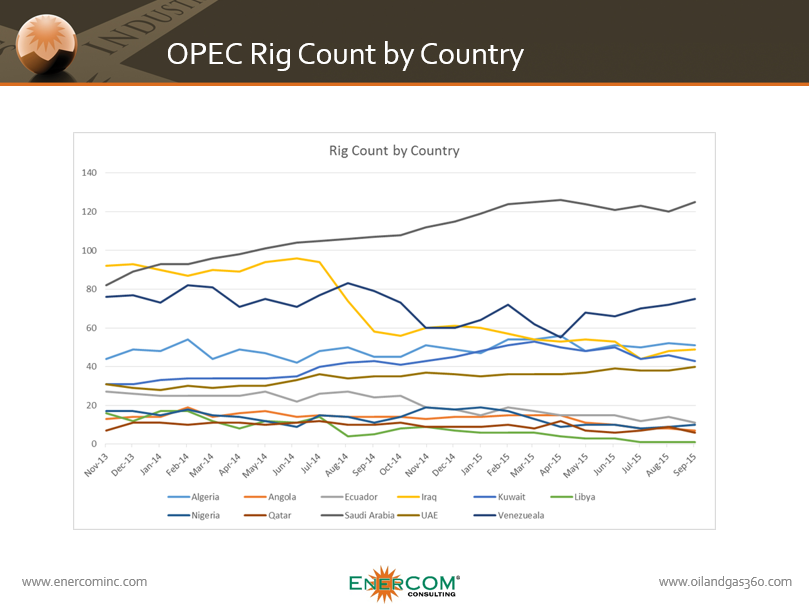

Information collected by Baker Hughes (ticker: BHI), which tracks the rig count both in the U.S. and abroad, shows a decline in the overall number of rigs in OPEC countries since November 2014, although the number of rigs in Saudi Arabia have continued to increase over that period of time.

OPEC’s rig count fell to 432 in November 2014 from its high of 458 in August 2014. The group’s total rig count climbed through February 2015, following the decision to maintain production, before dropping sequentially through July to a low of 405. OPEC has added rigs since then, with BHI’s data from September 2015 showing 418 rigs for the group.

The number of rigs varied from country to country, with most remaining steady or showing some decline. Saudi Arabia, the group’s largest producer, has continued to add rigs consistently from November 2013, through the Thanksgiving Day decision, and forward to today with only minor drops throughout. Iraq saw a substantial drop in its rig count from July to August 2014, with continued declines following the November decision.

A similar trend inside of OPEC emerged as was seen in the United States. As rig counts fell, production began to climb. In the months that followed Thanksgiving 2014, the production in most OPEC countries remained relatively flat, however, Saudi Arabia and Iraq (and to a lesser extent, Nigeria and the UAE) pushed total production higher until last month.

In OPEC’s November Oil Market Report (OMR), the group announced that its production fell slightly ahead of its December 4 policy meeting. The group’s production was down to 31.38 MMBOPD from the previous month, a 265 MBOPD decline due largely to lost production in Iraq from storms disrupting loading at the Basra oil terminal in the south of the country and sabotage reducing the flows through the Kurdish Autonomous Region.

Did the OPEC strategy work?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) released its annual World Energy Outlook with predictions on how OPEC’s strategy would affect its share of world oil markets. Based on the IEA’s estimates, OPEC’s share of world oil output will likely remain flat at 41% until 2020 in its base-case scenario. The Paris-based agency believes that the group’s share of production will then grow to 44% in 2025, and continue increasing to 49% of global oil output in 2040.

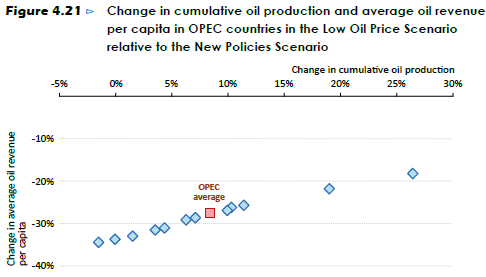

In the IEA’s New Policies base-case, released November 10, the IEA said that this scenario assumes $80 per barrel in 2020, but the agency was not able to rule out a low-price scenario, in which it saw OPEC production climbing higher, even as members collected less revenue from production.

In the low-price scenario, the IEA saw continued resilience in non-OPEC producers, including U.S. shale production, keeping prices in the $50-$60 per barrel range into the 2020s before edging higher toward $85 per barrel by 2040.

Lower prices fuel higher demand in the IEA forecasts, with overall volumes of inter-regionally traded oil trending 4 MMBOPD higher in the low-price scenario, and OPEC exports 6 MMBOPD higher, than in the New Policies scenario. Despite the larger export volumes, the lower price means OPEC would only see revenues of $1.3 trillion per year in 2040, $0.4 trillion less than in the New Policies base-case.

The IEA believes that the OPEC strategy worked, with the agency calling for the organization’s share of production to remain unchanged over the next four years before steadily increasing. Low oil prices will only further drive up OPEC’s output, but the strategy has a critical lynchpin, according to the IEA.

“All of the OPEC countries lose more from lower prices than they gain from higher volumes over the longer term,” the IEA wrote in its report. “This is one of the main reasons why a Low Oil Price Scenario looks less likely the further it is extended into the future: it relies on the active consent of the countries that are worst affected by the outcome. The assumed OPEC strategy of pursuing market share is effective, but ultimately also costly to the producers themselves.”

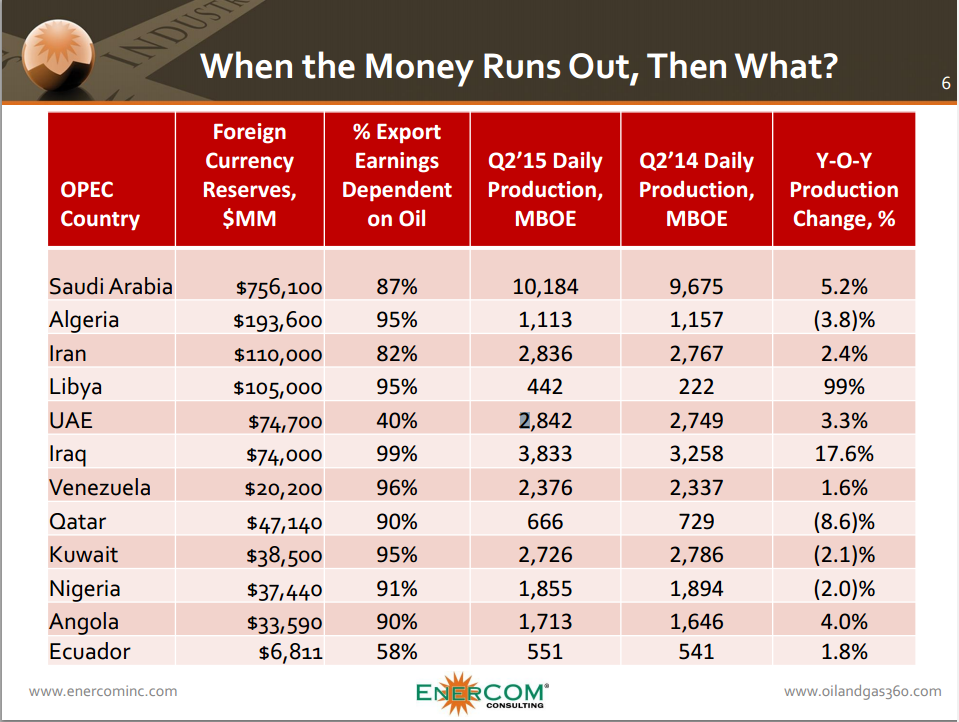

For OPEC to continue its current strategy, the members of the cartel that are the most directly affected by low oil prices must continue supporting a strategy that devalues their main source of income. Some OPEC members are adversely affected in a disproportionate way compared to the wealthier Persian Gulf members. Even those countries are being forced to rely on sovereign wealth funds in order to bridge the gap from lower revenues.

Who’s the real low cost provider?

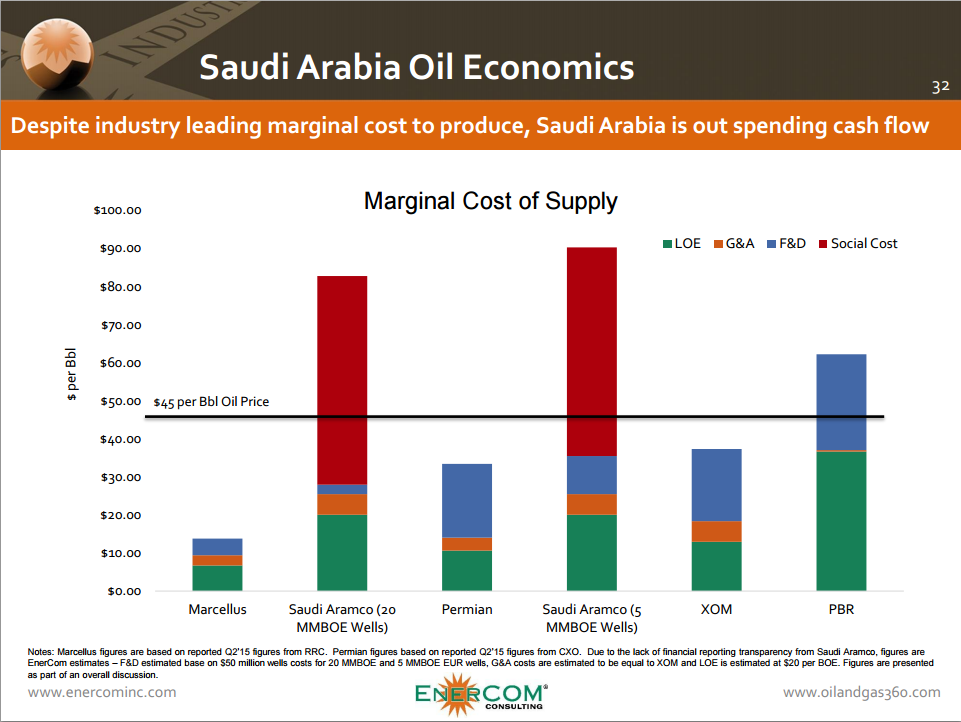

Despite continued rhetoric from OPEC to focus on lower cost production, including the cost of social programs, the cost for OPEC countries like Saudi Arabia are higher than in some of the most prolific basins in the United States.

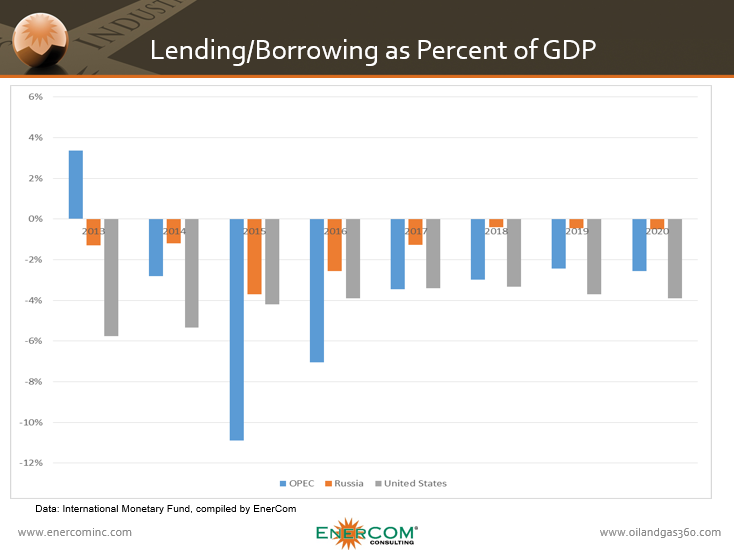

Lower commodity prices have hurt the economies of all of OPEC’s members considerably, with many needing to borrow money to bridge the budget gap. Libya, in particular, is expected to need large loans through the rest of the decade, with its borrowing as a percent of GDP reaching 68.15% this year, and an expectation that it will need to borrow 43.35% of its GDP next year as the country deals with both low oil prices and a civil war, according to the IMF. Venezuela is also expected to borrow substantial amounts of money, with the international lender of last resort projecting the country will borrow 20%-22% of its GDP through the end of the decade.

Other national economies that are strongly dependent on oil prices for income, such as Russia, will also be adversely affected by the continued downturn in the price of their main revenue-generating product. Russia’s borrowing as a percent of GDP is expected to decline faster than OPEC’s, however, with the country borrowing 3.69% of GDP this year, and then lowering that to about 0.5% by 2018.

The IMF forecasts that the U.S. will borrow less as a percent of GDP each year until 2018, when the fund sees borrowing at 3.34%, before increasing through the end of the decade to 3.91% in 2020.

This increased borrowing on the behalf of OPEC members is also expected to pull down the levels of savings the countries are putting back into their sovereign funds, unsurprisingly.

The heavy burden OPEC put on its own members by initiating a change in policy led less well-off members like Venezuela to publically call for a change of course. Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro went on a tour trying to convince other OPEC members that a price floor should be set by the group to ensure that development could continue.

“The minimum, minimum price should be $70,” said Maduro during his weekly program broadcast on state television. “Oil at $70 a barrel guarantees investments needed for global energy and economic stability.”

The dramatic fall in oil prices, along with the increasingly unstable fluctuations that followed, have left countries like Venezuela in a difficult spot. Venezuela relies on oil for 95% of its exports earnings and 25% of its GDP, leaving it highly exposed to changes in commodity prices.

Other members, particularly the Persian Gulf members like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, have stood by OPEC’s decision even as they had to draw on their sovereign wealth funds to bridge their spending gap. “I am sure that the decision was right and I am confident that the market will stabilize,” said UAE Energy Minister Suhail bin Mohammed Faraj Al Mazroui on November 18, 2015. “We are not regretting the decision we took, we had no option.”

The comment stands in stark opposition to one make by Nigeria’s former central bank governor Muhammad Sanusi II, who said OPEC’s decision was a mistake. “It does not help them and it does not help anyone,” he said.

Can OPEC adapt?

As the U.S. approaches its Thanksgiving holiday 2015, one day shy of a full calendar year since OPEC’s change in strategy crashed oil prices, we face a drastically different market. The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil on the Friday before Thanksgiving this year was just $44.66, 44% less than on the Friday before Thanksgiving 2014, when Brent stood at $80.36 per barrel. North American rig counts have more than halved in the same time frame.

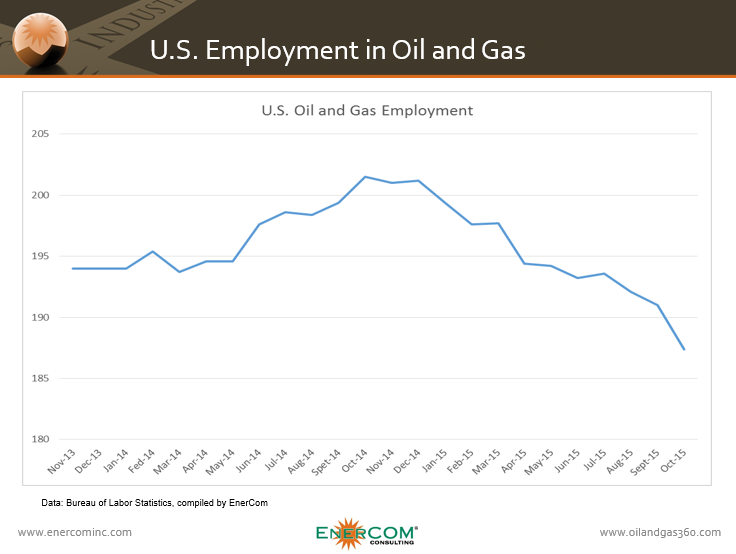

Employment in the U.S. oil patch was down 7% at the end of October compared to the same month last year, according to information from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Companies have cut jobs as they look to save costs in a market where the price of U.S. crude benchmark WTI traded at $40.39 on the Friday before Thanksgiving, down 47% from the week before Thanksgiving 2014, when a barrel of WTI was priced at $76.51.

U.S. producers have resorted to layoffs in response to the crude price decline, and Graves & Co., an industry consultant, believes roughly 250,000 people have been cut worldwide. The price decline in commodities caused a 23.4% drop in revenue (inclusive of realized hedging gains), with general and administrative expenses going down along with it, on a per BOE basis. In 2015, costs have declined to $4.95/BOE from $6.85/BOE in 2014 (a 27.7% decline), reflecting the “lean and mean” mentality being adopted in the new commodity environment.

OPEC continues to produce above its self-imposed ceiling of 30 MMBOPD, with the IEA forecasting that the group’s decision will likely lead to a larger portion of global market share going to the group, but only as long as its members continue to consent to a policy that damages their economies. Wealthier OPEC members like Saudi Arabia and the UAE continue to laud the decision as the only right move, while members like Venezuela see their main source of revenue run dry.

Next OPEC Meeting is Dec. 4

The organization’s next meeting is set for December 4, 2015, with many experts forecasting the group will maintain its current course in defending market share. While the immediate future shows no signs of changes, the last year has driven non-OPEC producers, particularly those in North America, to become increasingly efficient, avoiding an anticipated production decline along with a massive wave of bankruptcies and consolidation.

The flip side to OPEC’s new strategy of defending market share is that the longer the group focuses on keeping production high, the deeper it has to dig into its own wallet in order to continue covering the difference in lost revenue. Non-OPEC production proved to be far more resilient in the last year than many anticipated. Maintaining prices lower for longer may ultimately help OPEC achieve its goal of greater market share, but as non-OPEC producers adjust to the new market, the ill-effects of OPEC’s policy will become increasingly burdensome on the organization itself.

Whether or not a change in OPEC’s policy will come (and when it could be expected remains to be seen), U.S. production continues to hold near levels seen last November, even in the face of OPEC’s policy change.

OPEC Decision Created a New High Efficiency Producer: USA

Saudi’s oil minister called for a policy that would promote high efficiency producers, and in response, North American producers became more efficient.

For OPEC, the decision may have left the group with a flat market share through the end of the decade, but the overall cost of the decision is immense. Even wealthy members like Saudi Arabia are now in a precarious position. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) believes the country had spent $73 billion from its foreign reserves by September 2015, putting it on course to post a deficit of 19.5% of GDP this year, and spend the remainder of its reserves within five years, at the current rate.

With high social spending per barrel still continuing, and less well-off members like Venezuela lobbying for policy changes, it will be interesting to see if OPEC proves to be as adaptable as its rivals, or if it sowed the seeds of its own demise when it decided to push oil prices lower for longer on Thanksgiving .