Two stories below patch together the story of coal: Wyoming’s Cloud Peak Energy, EIA current count of coal mines in the U.S. and their production

2019 will be a pivotal year for Cloud Peak Energy

From the Gillette News Record

Cloud Peak Energy Corp.’s New Year’s resolution list for 2019 is short — survive.

Resolutions can run the gambit of clichés from advancing one’s career to losing weight to finally popping the question to a significant partner. It’s the same in business: expand, open new markets, develop new products and technologies, or all at once.

On the financial bottom line, they all have one common denominator — make more money.

That would be a good start for the Gillette-based thermal coal producer coming off a rocky 2018 that has the company on the brink of bankruptcy or possibly even insolvency.

“It’s been a horrible year operationally and a really hard year for the coal markets in general,” said Robert Godby, director of the Department of Economics and Finance at the University of Wyoming.

In the last 10 weeks, Cloud Peak has announced it’s exploring its financial “strategic alternatives,” including selling the company, to deal with a bottom line that’s bled nearly $215 million since 2015. Add a $400 million anvil of debt dangling overhead that’s coming due in the next few years and the only Powder River Basin-only coal producer was on shaky ground before a disastrous 2018 put Cloud Peak on the canvas for a possible 10-count.

“It’s definitely going to be a pivotal year for Cloud Peak Energy,” Godby said. “Then, if they get through this one, next year is also going to be a pivotal year. It’s going to be chewing the fingernails right up until the debt comes due.”

Golden eagles, excessive rain waged personal war on Cloud Peak’s flagship Antelope coal mine revenues

Many in the industry dubbed President Barack Obama’s administration as an eight-year “war on coal,” but Cloud Peak could consider 2018 as Mother Nature picking up where the Obama administration left off.

The first hit came early in the year when a group of nesting golden eagles delayed a crucial dragline move at the company’s flagship Antelope mine south of Wright. At 28.5 million tons of coal, Antelope alone accounted for nearly half of the 57.8 million tons Cloud Peak produced as a company in 2017.

Instead of taking four weeks, the dragline move took nine weeks, putting the mine behind schedule to meet its production and contract goals.

Then an unusually rainy spring caused spoil failure at the Antelope mine, putting it behind even more.

Between the eagles and mine repair, Antelope produced 23.1 million tons of coal last year, a 19 percent drop from 2017. Add a 23 percent decline in production at Cordero Rojo, its other Wyoming PRB mine, and profit margins that continue to narrow due to market conditions, many analysts are speculating if it’s game over for Cloud Peak.

“They’ve got a little bit of time to maneuver,” Godby said about the company’s outlook. “There’s a possibility they can do something with their creditors to gain some time. The way you might avoid bankruptcy is to try and arrange some kind of debt-equity swap. If that’s the case, then the mines keep running.

“They also basically need the market to turn around. They’re not generating income like they thought they would. The bottom line is they’ve done everything they can to consolidate their earnings.”

Those cost-saving moves have included terminating retirement health benefits and closing the Gillette administrative office and moving those operations to the Cordero Rojo mine site, Also, both Cordero Rojo and Antelope have been consolidated to run as a single operation.

Since spinning off from Rio Tinto Energy America in 2009, Cloud Peak’s financials read like a roller coaster: a steady, pleasant ride up a steep slope, then a scary plunge down.

From 2010, the company’s first full year as Cloud Peak, through 2014, it made a net profit of $611.7 million.

Then came a crash in 2015 that devastated thermal coal and pushed three of the Powder River Basin’s largest producers — Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal and Peabody Energy — into bankruptcy.

From 2015 through the first three quarters of 2018, Cloud Peak has lost $213.7 million, including a huge $204.5 million hit in 2015 alone. It’s $24 million in the red through the first nine months of last year.

Along with the company’s financial filings, including one Jan. 14 that moves to guard against any potential hostile takeover bids, there’s a lot to concern a community that relies on coal to drive its economy and Cloud Peak’s 1,224 employees.

Beyond the bottom line

Two years ago, the Boys & Girls Club of Campbell County was at a crossroads. Having installed a new board of directors and hired a new director, the club was beginning to rebuild itself into a stable, and eventually thriving, organization.

Already on shaky ground financially, it was the worst time for the club’s boiler to conk out. That’s when the club reached out to Cloud Peak Energy, which came through with a $20,000 donation that not only put the youth service group back in operation, it showed others in the business community that the Boys & Girls Club is worthwhile.

“They took a chance on us and we owe Cloud Peak a lot because of that,” said Noamie Niemitalo, the club’s board president. “If they hadn’t have taken the risk on us … we may not be still going and have turned it around.”

That $20,000 was hardly a one-time donation for the company. Cloud Peak paid for remodeling the club’s gymnasium and employees volunteered their time to paint the outside of the building, the former Lakeway Elementary School.

While Cloud Peak Energy generates headlines through its place as a major Powder River Basin coal producer, it’s also a major contributor to dozens of local nonprofits. It’s an impact that goes well beyond the more than 950 jobs it provides at its two Campbell County mines.

Cloud Peak gave $20,000 to the Donkey Creek festival to build a large concrete pad for the festival’s permanent stage. At the annual Charity Chili Cook-off, it regularly has teams entered in every category of the competition. And once a month, Cloud Peak feeds the patrons at the Campbell County Senior Center.

“That’s something they’ve been doing since the company used to be Rio Tinto,” said Ann Rossi, the senior center’s director. “They’ve been a huge support to the center, and not only the center but to the community.”

Cloud Peak has regularly bought animals raised by 4-H Club youth at the Campbell County Fair, then donated the animals to the Senior Center.

“When you ask, they find a way to make it happen,” Rossi said. “It makes you want to support them in return. They’ve gone through some tough times and you have to respect that they’re still trying to reach out and support the community even through all the challenges they have.”

If Cloud Peak were to have to shut down or were sold, “there would be a big void in our community,” Rossi said.

Cloud Peak denied a request for an interview for this story, but there were plenty of people willing to speak about its favorable influence in the community.

Campbell County Commission Chairman Rusty Bell agrees, saying Cloud Peak means more to the county than just the hundreds of jobs it provides.

“These are good people with good employment and these are high-paying jobs,” he said. “But they also support Gillette College and are just a good partner for everybody. They are just a really good company … and really care about people.

“We hope and pray they have a better year and they see some light at the end of the tunnel and things pick back up.”

The thought of Campbell County without Cloud Peak Energy is something Gillette Mayor Louise Carter-King said she’s just not ready to consider.

“I don’t feel like going there,” she said. “I just can’t imagine them shutting their doors, because it would trickle down to every facet (of life and business here). I just can’t dwell on what might happen.”

Not all gloom and doom

The inevitable demise of Cloud Peak also isn’t something a number of energy analysts are ready to admit.

Bob Burnham is the founder of Colorado-based Burnham Coal LLC and is a longtime observer of the Powder River Basin. Although the company is teetering, he’s not convinced it’s reached a tipping point.

“You can’t hide it if things are really bad,” he said, adding that they are for Cloud Peak Energy. Still, “I’m not ready to write them off just yet. They had a really bad streak of luck last year from that eagle’s nest to the rain. It’s just a bad string of luck.

“I hear through the rumor mill they think they’ve fought their way through that. Hopefully, that bad luck streak is finished.”

Asked if he can see any scenarios where Cloud Peak survives, Burnham said there are “a number of things that can happen.”

One is bankruptcy, which Burnham said may not be such a bad thing. He uses Arch, Alpha and Peabody as examples. Each were able to get rid of and regulate billions of dollars of debt and are now showing strong financials even as the market conditions continue to tighten for thermal coal.

“They can turn it around and I’m not ready to write that off, but I don’t think they can handle another year like 2018,” he said. “But,I think they can survive it and continue as a going entity.”

One of those pivotal points in 2019 will be Cloud Peak’s year-end report and earnings call for 2018, which hasn’t yet been announced. That’s where the company will give more insight into its ongoing financial struggles and outlook for the rest of the year.

After what Campbell County and the rest of Wyoming experienced a couple of years ago with the collapse of the coal market, Burnham said he can understand why Campbell County residents “would be really concerned.”

The company’s failure “would have a real bad impact on Gillette and Campbell County, and probably down into Douglas and Converse County,” he said.

How Cloud Peak survives

One thing the company and community shouldn’t do now is panic, Godby said. Cloud Peak isn’t likely to close suddenly one morning without warning.

“They have a little bit of time and there’s no need to rush it,” Godby said, adding a number of undecided elements could help the company. “Will there be a big change in the market? Could there be a coal bailout from the federal government with a Trump administration still in power? People still have hope.”

Ultimately, Cloud Peak’s future is tied to the thermal coal market, he said. With production now around 300 million tons a year in the Powder River Basin, the question becomes into how many pieces can you cut a steadily shrinking pie that’s about 33 percent smaller than a decade ago.

“That’s the big question looming over the basin — what’s going to happen to the capacity out there?” Godby said.

He used the example of a hunt on the African plains, where predators look for the weakest animal in a pack.

“The lions are circling the herd looking for the weakest to take advantage of. The expectation is Cloud Peak is currently the weak one,” he said. “Without that, they could probably hunker through the storm and hope that something turns around.”

Whether Cloud Peak Energy’s shareholders will be willing to hunker down as well is another question, Godby said. The company’s stock closed at 41 cents a share Friday and continues a streak of consecutive weeks trading below $1 going back to November. At this time last year, Cloud Peak was trading at more than $5.20 a share.

“The people who are most at risk with Cloud Peak (financially) now are the common shareholders,” he said. “If they didn’t get off the train before, it’s too late now. The market is basically pricing the company at a bankruptcy.”

Acquiring the company also can be problematic for potential buyers, he said. The most likely candidates would seem to be Arch Coal and Peabody Energy, two of the largest coal producers in the world that also operate mines adjacent to Cloud Peak’s in the PRB. But both companies are relatively fresh out of their own bankruptcies and the demand for thermal coal may not warrant the move.

“If you take over Cloud Peak right now, you have to take over their debt,” Godby said. “It’s not very likely anybody’s going to want to buy them with that given the fact you just wait a couple of years and see if those assets come on the market a lot cheaper anyway.

“It’s been a horrible year operationally and a really hard year for the coal markets in general, and then you’re a year closer to that deadline when the debt is due. Right now, it looks like with the cash (Cloud Peak) is generating, it can be really problematic.”

Around for the evolution?

As Cloud Peak Energy fights for its financial survival, Bell said he’s hopeful the company can hang on long enough to take advantage of some of the potential breakthroughs and carbon-based industries that are in the future for the Powder River Basin.

“That’s really important,” Bell said about the research to diversify the carbon industry. “Cloud Peak has been a great community member and the employees are great people in Campbell County.”

With efforts like the carbon capture and reuse research happening at the Integrated Test Center to other initiatives to develop other products and uses for the area’s abundant carbon resources, Bell said digging coal in the PRB could someday fuel much more than power plants.

He just hopes Cloud Peak can weather the storm to see those sunnier days.

From Cloud Peak Energy – Jan. 30, 2019

Cloud Peak Energy Provides Update on Strategic Alternatives Review

Cloud Peak Energy Inc. (NYSE: CLD) (the “Company”), the only pure-play Powder River Basin (“PRB”) coal company, today announced that it has retained Centerview Partners LLC as its investment banker, Vinson & Elkins LLP as its legal advisor, and FTI Consulting, Inc. as its financial advisor to assist the Company and its Board of Directors in the Company’s review of capital structure and restructuring alternatives. During this review process, the Company’s mines will continue normal operations, safely and efficiently meeting our customer commitments.

As disclosed on November 13, 2018, the Company’s Board, working together with its management team and legal and financial advisors, commenced a review of strategic alternatives, including a potential sale of the Company, and previously engaged J.P. Morgan Securities LLC as its financial advisor and Allen & Overy LLP as legal counsel in connection with exploring sale opportunities.

The Company’s Board has not set a specific timetable for this review process and the Company does not intend to provide updates unless or until it determines that further disclosure is appropriate or necessary.

In connection with this review process, the Company’s Board approved an updated executive retention program for the Company’s senior management team, which replaces the previously announced November 2018 retention program. Additional information on the retention program can be found in the Company’s Form 8-K filed today.

About Cloud Peak Energy®

Cloud Peak Energy Inc. (NYSE:CLD) is headquartered in Wyoming and is the only pure-play Powder River Basin coal company. As one of the safest coal producers in the nation, Cloud Peak Energy mines low sulfur, subbituminous coal and provides logistics supply services. The Company owns and operates three surface coal mines in the PRB, the lowest cost major coal producing region in the nation. The Antelope and Cordero Rojo mines are located in Wyoming and the Spring Creek Mine is located in Montana. In 2017, Cloud Peak Energy sold approximately 58 million tons from its three mines to customers located throughout the U.S. and around the world. Cloud Peak Energy also owns rights to substantial undeveloped coal and complementary surface assets in the Northern PRB, further building the Company’s long-term position to serve Asian export and domestic customers. With approximately 1,300 total employees, the Company is widely recognized for its exemplary performance in its safety and environmental programs. Cloud Peak Energy is a sustainable fuel supplier for approximately two percent of the nation’s electricity.

From the EIA Today in Energy – Jan. 30, 2019

More than Half of the U.S. Coal Mines Operating in 2008 have Since Closed

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-7A, Annual Survey of Coal Production and Preparation, and U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration Form 7000-2, Quarterly Mine Employment and Coal Production Report

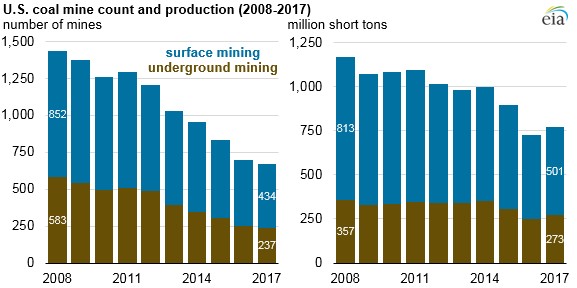

In the United States, decreasing demand for coal has contributed to lower coal production, which has fallen by more than one-third since peak production in 2008. As U.S. coal demand has declined, the number of active coal mines has decreased by more than half, from 1,435 mines in 2008 to 671 mines in 2017. As the U.S. market contracted, smaller, less efficient mines were the first to close, and most of the mine closures were in the Appalachian region.

Although underground mines had a larger percentage of closures from 2008 to 2017 (60% versus 49% of surfacemines), surface mines have seen larger declines in production, falling 39% compared with 24% for underground mines. Most coal regions contain a mix of both surface and underground mines, except for the Powder River Basin in southeast Montana and northeast Wyoming, where large surface mines account for more than 40% of total U.S. production.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-7A, Annual Survey of Coal Production and Preparation, and U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration Form 7000-2, Quarterly Mine Employment and Coal Production Report

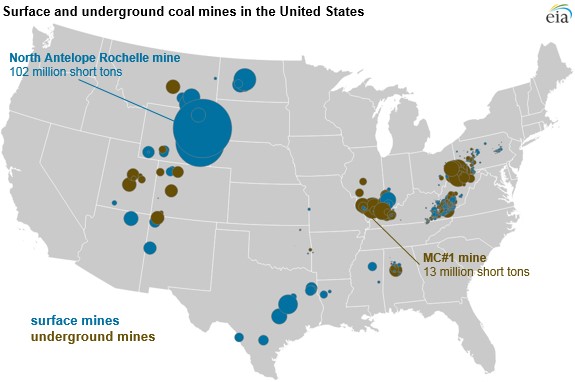

The Appalachian and Illinois Basins east of the Mississippi River have the most mines in the country, with more than 77% of eastern production coming from underground mines. Between 2008 and 2017, 340 fewer underground mines produced coal in this region, compared with 410 fewer surface mines. In contrast, basins in the west—primarily the Powder River Basin—have fewer mines, and production mainly comes from a smaller number of large surface mines.

The uptick in mine closures since 2008 has largely been driven by economics, and smaller, less profitable mines have been more susceptible to closures. Several factors dictate the profitability of mines, including the method used to extract the coal.

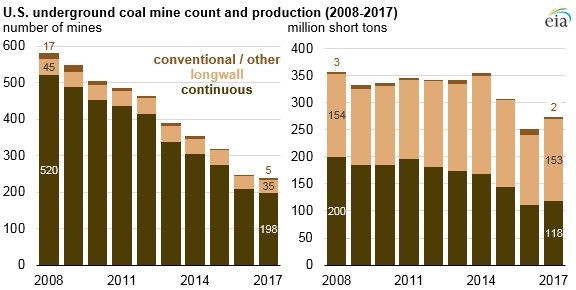

Underground mining uses three different methods: longwall, continuous, and conventional.

Longwall mining uses an automated cutting machine, and the broken coal is transported to the surface on a conveyor system. Roof supports are moved as the machine advances, allowing the roof to fall once an area is mined out. Longwall mining has high recovery and extraction rates and is the most productive type of underground mining, but it can only be used in flat, thick, and uniform coalbeds.

Continuous mining is a form of mining called room and pillar mining, in which a continuous mining machine extracts and removes coal from the working face in one step with no blasting required. Pillars of coal are left to support the roof between areas where coal is mined.

Conventional mining is a form of room and pillar mining that consists of three steps: cutting the coal, blasting the coal, and then loading the broken coal. This category also includes other miscellaneous mining methods, such as shortwall, scoop loading, and hand loading.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-7A, Annual Survey of Coal Production and Preparation, and U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration Form 7000-2, Quarterly Mine Employment and Coal Production Report

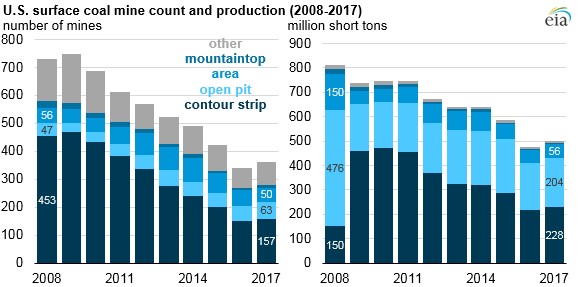

Surface mining techniques are categorized as either strip, open pit, or mountaintop removal.

Strip mining is a method used on flat terrain and involves removing soil or rock above a layer of coal, exposing the coal seam for mining. One type of strip mining is contour mining, where extraction activities occur on a hillside. Another method, area mining, occurs on relatively flat terrain. Contour strip mining accounted for more than half of the surface mine closures between 2008 and 2017.

Open-pit coal mining is a combination of contour and area mining methods and is used to mine thick, steeply inclined coalbeds. In contrast to other forms of mining, open pit mines increased in number from 2008 to 2017, but production levels still fell.

Mountaintop mining is sometimes considered a variation of contour mining and involves removing the mountaintop, or the overburden (rock or soil overlying a mineral deposit), which creates a level plateau or gently rolling contour and exposes entire coal seams running through the upper portion of a mountain. Mountaintop mines are relatively few in number compared with contour strip, open pit, and area mines. Production levels at mountaintop mines are similarly small.

Other surface mining methods account for very small shares of coal production. Although the number of mines using these methods are nearly as numerous as the combination of area and open mines, production remains small.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Form EIA-7A, Annual Survey of Coal Production and Preparation, and U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration Form 7000-2, Quarterly Mine Employment and Coal Production Report