The oil market is facing uncharted territory as the drop-off in demand, caused by the coronavirus pandemic, combined with rapidly filling storage, sent prices plunging into negative territory for the first time in history.

And with only guesswork as to when stay-at-home orders might be lifted and when crude demand might pick up, traders warn that oil could continue to trade at extremely depressed levels.

“If we have not recovered from Covid in July so that enough driving has come back and storage is full, then the price of crude oil is going to be zero,” RBN Energy’s Rusty Braziel told CNBC. He called Monday’s trading activity “insane,” and said that in his more than 40 years of trading he had “never seen anything like this.”

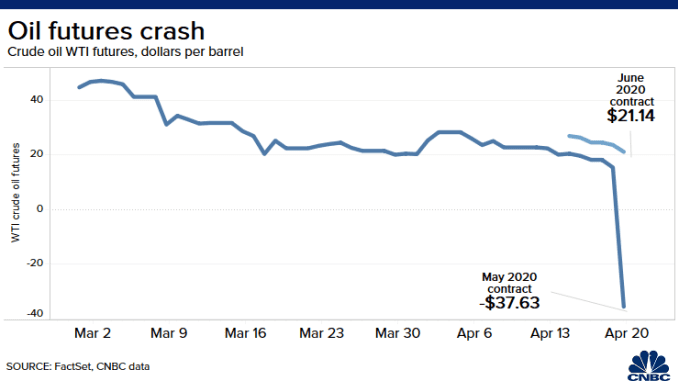

West Texas Intermediate crude for May delivery fell Monday more than 100% to settle at negative $37.63 per barrel, meaning sellers would effectively pay to have the oil taken off their hands. The contract expires on Tuesday, fueling the wild swing to the downside as traders scrambled to get out of their positions.

Longer-term contracts settled above $20 per barrel on Monday, but losses accelerated in overnight trading, suggesting that traders are increasingly concerned about a lack storage will continue in coming months.

The contract for June delivery — the most actively traded WTI contract — fell 18.7% to trade at $16.61 per barrel on Tuesday. The July contract was about 10% lower at $23.66 per barrel.

Bernadette Johnson, Enverus’ vice president of strategic analytics, noted that the June contract will likely face pressure until demand comes back, and she believes it will “start coming down over the next month.”

Some of this view is already reflected with bets in the options market. Scott Nations, president and chief investment officer at NationsShares, noted that June 0.50 puts are currently trading for more than 50 cents, meaning that traders would only turn a profit if the June WTI contract expires in negative territory when accounting for the option premium.

In the meantime, Johnson said a lack of storage will force oil companies to halt production.

“What we’re into now is shut-in economics,” she told CNBC in an email. “Product demand is off and when product demand is off, you don’t buy crude. If you don’t buy crude, you can’t produce the crude if there’s not a place to store it, and so that’s the problem.” In the near-term, she sees WTI hovering around the $10-$12 level.

Pointing to insufficient pipeline and storage capacity, analysts at Deutsche Bank said prices could remain in negative territory before rebounding. “Continued pressure on infrastructure may result in negative pricing at some point again before the end of May, on the current trajectory,” analyst Michael Hsueh said.

The fall in oil prices has been swift and steep as the coronavirus pandemic has led to unprecedented demand loss. People aren’t driving or flying, meaning there’s no use for millions of barrels of oil. Meanwhile, inventories are building. On Wednesday the U.S. Energy Information Administration said that for the week ending April 10 stockpiles rose by a record 19.2 million barrels.

Amid this unfavorable backdrop Goldman Sachs believes that volatility will remain “exceptionally high” in the coming weeks, but that shut-ins will ultimately lead to price stabilization.

“This inflection will play out in a matter of weeks, not months, with the market likely forced to balance before June,” Goldman analysts led by Damien Courvalin said in a note to clients Monday.

Just one week ago OPEC and its oil-producing allies agreed to a historic output cut that would take 9.7 million barrels per day off the market. But oil closed in negative territory the next day, signaling that the cuts, which begin May 1, are simply not enough to combat the fall-off in demand. The International Energy Agency warned in its closely-watched monthly oil report that demand in April could be 29 million barrels per day lower than a year ago, hitting a level last seen in 1995.

Analysts at Citi said that while supply and inventories should tighten in the second half of the year, the short-term could see more price swings.

“The next 4-6 weeks are seeing severe storage distress, likely to drive wild price realizations and unusual disconnects, including supercontango and negative prices,” the analysts led by Eric Lee said in a note to clients Monday. Contango is when longer-dated contracts trade at a premium to current contracts.

In the meantime, as uncertainty about when global economies will be back up and running reigns supreme, Braziel could only attribute any optimism in the higher-priced longer-term contracts to one belief: “hope springs eternal.”

[contextly_sidebar id=”gJTtbTWwNX5ThpfyxTXtV17tlYjxqPZX”]