Direction of state’s oil and gas regulator awaits high court review of Martinez decision

In May, the Colorado Attorney General petitioned the Colorado Supreme Court to review the appellate court’s ruling in the case of Martinez v. Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, after the appeals court overturned a lower court ruling.

The lower court ruling favored the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC), confirming that the commission did not have to comply with the Martinez et al petition for a rulemaking.

The effect of the lower court ruling was that COGCC could continue permitting and regulating oil and gas in Colorado the way it always has—by balancing the fostering of responsible oil and gas development with safeguarding the public health, safety and welfare.

The petitioners, a group of climate activist youths, took the case to the Colorado Court of Appeals. The Martinez petitioners and their attorneys argued that the COGCC had a separate duty to protect health, safety and welfare and environment, rather than providing a balance of the commission’s two mandates. Two of the three appellate court judges agreed with the interpretation and overturned the lower court in a two-to-one decision.

The decision by the appellate court, if allowed to stand, would change how the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) approaches its duty to carry out the law that created it.

Martinez and fellow petitioners sought to have COGCC impose a rule that would entirely prohibit permitting of oil & gas activity in the state unless the COGCC could assure zero environmental, climate impact

The beginning of the Martinez v. COGCC case dates back to November 15, 2013, when petitioners Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, Itzcuahtli Roske-Martinez, Sonora Brinkley, Aerielle Deering, Trinity Carter, and Emma Bray, minors appearing by and through their legal guardians Tamara Roske, Bindi Brinkley, Eleni Deering, Jasmine Jones, Robin Ruston, and Diana Bray, petitioned the COGCC to impose a rulemaking as recapped on April 22, 2014, in a memorandum to the COGCC commissioners from COGCC Director Matthew Lepore.

The petition requested of the COGCC to promulgate “a rule to suspend the issuance of permits that allow hydraulic fracturing until it can be done without adversely impacting human health and safety and without impairing Colorado’s atmospheric resource and climate system, water, soil, wildlife, other biological resources.”

Lepore’s memo went on to say, “The Petitioners request the Commission to take the following specific actions ‘to protect the health and safety of Colorado’s residents and the integrity of Colorado’s atmospheric resource and climate system, water, soil, wildlife, other biological resources, upon which all Colorado citizens rely for their health, safety, sustenance, and security’:

(1) Evaluate the impacts of oil and gas drilling on trust resources and human health according to the best available science before issuing any permits for oil or gas drilling or exploration;

(2) Adopt a climate recovery plan by March 15, 2014, based on the best available science that fulfills the Commission’s duty to protect trust assets from impairment;

(3) Publish annual reports, which must be verified by an independent third-party, on statewide greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas industry on the Commission’s website for public review;

(4) Adopt any necessary policies or regulations necessary to implement the proposed action detailed in sections (1), (2), and (3) above.”

Boulder’s Earth Guardians behind the Martinez case

The memo said the eight petitioners describe themselves as “youth, who represent the youngest living generation of public trust beneficiaries, and have a profound interest in ensuring that the climate remains stable enough to ensure their right to a livable future.” Six of the eight petitioners identified themselves as members of Earth Guardians, a Boulder, Colorado-based climate activist organization. Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, Earth Guardians youth director, is described on the Earth Guardians website as a 17-year-old “indigenous climate activist.”

The website says that Martinez has been involved with “moratoriums on fracking in his state and is currently a plaintiff in a youth-led lawsuit against the federal government for their failure to protect the atmosphere for future generations.”

Colorado AG steps in, requests that appellate court decision be reviewed by Colorado Supreme Court

The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) voted to take the ruling to the Colorado Supreme Court. Amidst appeals by Gov. John Hickenlooper to not petition for the high court review of the ruling, Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman nonetheless officially petitioned the high court to review the appeals court reversal of the lower court.

Adding more background in the AG’s request for a supreme court review, Coffman’s petition contains the following statement regarding the appeals court decision:

“… the court of appeals rejected the Commission’s long-settled interpretation [of its mandate as set forth by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act].

“In a published 2–1 decision, the court held that rather than balancing competing public policies, the Act prioritizes one policy at the expense of others. Under this view, the Commission is permitted to disregard the Act’s directive to foster responsible oil and gas development and enact rules that would entirely prohibit oil and gas related activity unless it can occur with zero direct or cumulative environmental impact.”

By petitioning the Colorado Supreme Court for Writ of Certiorari, Attorney General Coffman and the COGCC are asking the high court to review the appellate court ruling.

Supreme Court’s review of Martinez v. COGCC appeals court ruling could have significant impact on the oil and gas industry

If the Supreme Court either refuses to review the case, or if it does review and subsequently allows the appeals court decision to stand, the result would deliver wide-ranging consequences as to how the COGCC could permit oil and gas activity in Colorado going forward.

A Colorado Supreme Court ruling that supports the appellate court’s decision would essentially introduce a new interpretation of the COGCC’s longstanding mandate to balance responsible oil and gas development with public health, safety and welfare.

In plain language, new oil and gas development in Colorado could grind to a halt if the appellate court decision on Martinez v. COGCC stands.

What’s next in Martinez v. COGCC?

The Colorado Supreme Court is the court of last resort in the Colorado court system. According to the Colorado Supreme Court website, “An individual who has appealed to the Court of Appeals and is still dissatisfied may ask the Supreme Court to review the case. In most situations, the Supreme Court has a right to refuse to do so. In some instances, individuals can petition to the Supreme Court directly regarding a lower court’s decision.”

In the Martinez v. COGCC case, it is the COGCC that petitioned the Supreme Court directly, following the appellate court ruling that would change how it approaches the mandate it has to carry out the provisions of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act.

Colorado Supreme Court history with certiorari petitions

In fiscal year 2015, a total of 1,549 cases were filed with the Supreme Court. About 70% were certiorari petitions seeking review of intermediate appellate court (primarily Court of Appeals) decisions, according to the Supreme Court—like the COGCC v. Martinez petition.

High court grants review in only about 10% of petitions

“The Supreme Court generally does not grant discretionary review simply to correct an erroneous decision that will affect only the parties to that case. Instead, because the Court’s primary role in reviewing such decisions is to set precedent that develops and clarifies the law on important issues of broad impact, it grants review in a small percentage of cases,” the Court said.

“That the Commission was supported by multiple industry players and representatives, including the American Petroleum Institute, indicates that the case was in front of the Court in a full treatment, as opposed to being an obscure case where the issue was not fully recognized or developed by the parties,” Haynes and Boone energy attorney Robert Thibault told Oil & Gas 360®.

The Court said on its website that it has no set number of certiorari petitions it will grant, but it typically grants less than ten percent of the petitions filed each year.

But a review seems likely based on the Court’s self-defined role “to set precedent that develops and clarifies the law on important issues of broad impact.” Upholding the appellate court’s decision would have broad impact on the oil and gas industry and some of the U.S.’s more important hydrocarbons producing basins—the Piceance basin in western Colorado and the DJ basin on the east side of the continental divide in northern Colorado.

The DJ basin, with Weld County at ground zero northeast of Boulder, is home of the Wattenberg field, thousands of oil and gas leases, hundreds of operators, thousands of wells and future drilling sites within the inventories of key independent oil and gas operators seeking to develop the Niobrara A, B and C and Codell shale plays using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing.

Decision to uphold would be an extremely consequential outcome for the industry

Haynes and Boone attorney Robert Thibault told Oil & Gas 360® that the Colorado Court of Appeals “held that the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act, the law that provides the fundamental authority to the COGCC to regulate oil and gas operations in the state, does not provide that the Commission can base its regulations on a balance between oil and gas production and public health, safety and welfare, but instead requires that it is a mandatory duty of the Commission to promulgate regulations that are consistent with the public health, safety and welfare as an absolute requirement without any balance between the two.”

In question: COGCC’s directive to balance between fostering responsible oil and gas production and public health, safety and welfare – the court’s reinterpretation

“This decision [by the appellate court] rejected the COGCC’s own interpretation of its rulemaking duties that has been traditionally recognized—that is, that a balance was required between production and public health, safety and welfare,” Thibault told Oil & Gas 360®.

“Notably, the Court of Appeals based its decision on language in the section of the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Act setting out the declaration of the broad legislative intent, not on the more clearly worded sections that specified the nature and scope of the commission’s rulemaking duties,” Thibault said.

Crux of the appeals court decision

Thibault cautioned that court was not ruling on the merits of the Martinez proposed rulemaking content. “The [Appeals] Court expressly stated that it was not ruling on the merits of the activists’ proposal,” Thibault said. “[It was] only rejecting the Commission’s refusal to consider beginning a rulemaking on the grounds that the COGCC was misinterpreting the Act (that is, the Commission interpreted the Act to require a balancing of production and public health, safety and welfare, and that was sufficient grounds to reject the activists’ proposal).”

Extremely consequential outcome

“There was a strong dissent that may well form the basis for a Supreme Court decision that goes the other way by reinstating the Commission’s prior reliance on balancing the two interests,” Thibault said. “Ultimately the Colorado legislature is the final arbiter for clarifying the proper result. However, until either of those happens, this decision needs to be considered an extremely consequential outcome as it would serve to upend the well-established commission practice of balancing production with public health, welfare and safety.”

Judge Booras’ dissenting conclusion

Three judges heard the Martinez case for the Colorado Court of Appeals, the court that issued the reversal of the district court which upheld the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission’s decision to refuse the Martinez request for rulemaking. They are Judges Fox, Vogt and Booras. Fox and Vogt represented the concurring majority opinion in the decision to reverse the lower court.

Booras gave the lone dissenting opinion. In her dissent, Judge Booras wrote the following as she concluded her dissenting opinion:

“The Commission has consistently recognized its duty to balance health and environmental concerns.

“Our supreme court noted in City of Fort Collins v. Colorado Oil & Gas Association, 2016 CO 28, that, consistent with its legislative authorization, “the Commission has promulgated an exhaustive set of rules and regulations ‘to prevent waste and to conserve oil and gas in the State of Colorado while protecting public health, safety, and welfare.’ Dep’t of Nat. Res. Reg. 201, 2 [Code Colo.] Regs. 404–1 (2015).”

“For these reasons,” Judge Booras said, “I would affirm the district court’s order upholding the Commission’s order denying Petitioners’ petition for rulemaking. In concluding that the district court order should be affirmed, I would also reject the Petitioners’ constitutional arguments based on the public trust doctrine and that the Commission’s interpretation of the Act is an unconstitutional infringement of Petitioners’ natural rights to enjoy their lives and liberties, protect their property, and obtain their safety and happiness. The Colorado Supreme Court declined to apply the public trust doctrine in City of Longmont v. Colorado Oil & Gas Association, 2016 CO 29.”

Colo. Supreme Court and oil and gas cases: state high court has overturned 2 local frac bans based on state law that defines the role of the COGCC

While the Martinez case is different from prior cases that challenged municipal frac bans, it’s pertinent to look at the high court’s decisions on oil and gas issues. The Colorado Supreme Court has overturned two municipality-imposed frac bans—Longmont, Colo. and Fort Collins, Colo.

In its review of the Fort Collins fracing moratorium case, the Colorado Supreme Court said:

“The question thus becomes whether the Oil and Gas Conservation Act preempts Fort Collins’s moratorium because of an operational conflict.

“The state’s interest in oil and gas development is expressed in the Oil and Gas Conservation Act and the rules and regulations promulgated thereunder by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (the Commission), which is the state agency tasked with administering the Act’s provisions. See § 34-60-104.5(2)(a), C.R.S. (2015).

“The Act declares: ‘It is the intent and purpose of this article to permit each oil and gas pool in Colorado to produce up to its maximum efficient rate of production, subject to the prevention of waste, consistent with the protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources, and subject further to the enforcement and protection of the coequal and correlative rights of the owners and producers of a common source of oil and gas, so that each common owner and producer may obtain a just and equitable share of production therefrom.’ § 34-60-102(1)(b), C.R.S. (2015).

“Pursuant to the Act, the Commission is empowered to make and enforce rules, regulations, and orders, § 34-60-105(1), C.R.S. (2015), and to regulate, among other things, the “drilling, producing, and plugging of wells and all other operations for the production of oil or gas,” the “shooting and chemical treatment of wells,” and the spacing of wells, § 34-60-106(2)(a)–(c), C.R.S. (2015).”

In its final opinion, the Colorado Supreme Court said:

“The Supreme Court concludes that Fort Collins’s five-year moratorium on fracking and the storage of fracking waste within the city is a matter of mixed state and local concern and, therefore, is subject to preemption by state law. Applying well-established preemption principles, the court further concludes that Fort Collins’s moratorium operationally conflicts with the effectuation of state law.

“Accordingly, the court holds that the moratorium is preempted by state law and is, therefore, invalid and unenforceable. The court thus affirms the district court’s order invalidating the moratorium and remands this case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.”

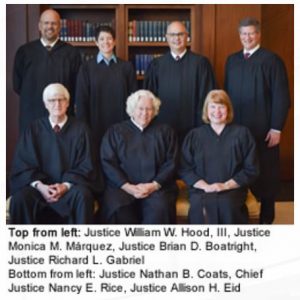

Makeup of the Colorado high court

The Colorado Supreme Court is comprised of seven justices appointed by the governor pursuant to Colorado’s merit selection process. The seven justices on the Colorado Supreme Court are all extremely high-achieving, accomplished attorneys, by training and experience.

Chief Justice Nancy E. Rice: Date of Judicial Appointment: August 5, 1998 – by Governor Roy Romer (D)

Became Chief Justice: January 8, 2014

Appointed to the Colorado Supreme Court on August 5, 1998.

Denver District Court Judge, 1987 to 1998. Assistant U.S. Attorney, District of Colorado, 1977 to 1987. Deputy Chief of Civil Division of U.S. Attorney’s Office from 1985 to 1987. Deputy State Public Defender, Appellate Division, From 1976 to 1977. Law clerk for Judge Fred Winner, U.S. District Court, District of Colorado, 1975 to 1976. Adjunct Professor of Law, trial advocacy, University of Colorado School of Law, 1987 to present.

Born June 2, 1950 in Boulder, Colorado. Grew up in Colorado and Cheyenne, Wyoming. Received Bachelor of Arts cum laude from Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts, in 1972. Received J.D. from University of Utah College of Law in 1975.

Justice Nathan B. Coats: Date of Judicial Appointment: April 24, 2000 – by Gov. Bill Owens (R)

Appointed to the Colorado Supreme Court, April 24, 2000.

Chief Appellate Deputy District Attorney for the Second Judicial District (Denver)1986 to May 2000; Adjunct Professor, University of Colorado School of Law (Constitutional Criminal Procedure) Fall of 1990; Deputy Colorado Attorney General, Appellate Section, 1983 to 1986; Assistant Colorado Attorney General, Appellate Section, 1978 to 1983; Associate, Hough, Grant, McCarren and Bernard, 1977 to 1978.

Justice Allison H. Eid: Date of Judicial Appointment: February 15, 2006 – by Gov. Bill Owens (R)

Sworn in as the 95th Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court on March 13, 2006.

Before joining the Court, Justice Eid was the Solicitor General of the State of Colorado, serving as the chief legal officer to the Colorado Attorney General and representing Colorado officials and agencies in state and federal court. She was also a tenured Associate Professor of Law at the University of Colorado School of Law, teaching Constitutional Law, Legislation, and Torts, and writing on the topic of constitutional federalism.

Prior to joining the faculty of the University of Colorado School of Law, Justice Eid practiced commercial and appellate litigation with the Denver office of the national law firm of Arnold & Porter. She clerked for the Honorable Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and for Judge Jerry E. Smith of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Houston, Texas.

Justice Eid earned her bachelor’s degree in American Studies (With Distinction and Phi Beta Kappa) from Stanford University in 1987. She then served as a Special Assistant and Speechwriter to U.S. Secretary of Education William J. Bennett. In 1991, she graduated with High Honors from The University of Chicago Law School, where she was Articles Editor of The University of Chicago Law Review and was elected to the Order of the Coif. In 2002, President George W. Bush appointed her to serve on the Permanent Committee for the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise, established by Congress in 1955 to prepare the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Justice Eid grew up in Spokane, Washington.

Justice Monica M. Márquez: Date of Judicial Appointment: September 8, 2010 by Gov. Bill Ritter (D)

Sworn in as Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court on December 10, 2010

Monica M. Márquez was appointed by Governor Bill Ritter, Jr. Before joining the Court, Justice Márquez served as Deputy Attorney General at the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, where she led the State Services section in representing several state executive branch agencies and Colorado’s statewide elected public officials, including the Governor, Treasurer, Secretary of State, and Attorney General. During her tenure at the Attorney General’s Office, Justice Márquez also served as Assistant Solicitor General and as Assistant Attorney General in both the Public Officials Unit and the Criminal Appellate Section. Prior to joining the Attorney General’s Office, Justice Márquez practiced general commercial litigation and employment law at Holme Roberts & Owen, LLP.

Justice Márquez was born in Austin, TX. She grew up in Grand Junction, CO, where she graduated from Grand Junction High School. She earned her bachelor’s degree from Stanford University, then served in the Jesuit Volunteer Corps as a volunteer inner-city school teacher and community organizer in Camden, NJ, and Philadelphia, PA. She graduated from Yale Law School, where she served as Editor of the Yale Law Journal, Articles Editor of the Yale Law & Policy Review, and co-coordinator of the Latino Law Students Association. Upon graduation, she clerked for Judge Michael A. Ponsor of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts in Springfield, MA, and for Judge David M. Ebel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in Denver, CO.

Justice Brian D. Boatright: appointed as District Court Judge, June 16, 1999 by Gov. Bill Owens (R)

Sworn in as Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court on November 21, 2011, by Governor John Hickenlooper (D)

Before joining the Supreme Court, Justice Boatright was a District Court Judge in the First Judicial District in Golden, Colorado and had been appointed to that position on June 16, 1999 by Governor Bill Owens. As a District Court Judge, Justice Boatright presided over Felony Criminal matters, Probate matters, Civil Cases matters, Dependency & Neglect matters and Juvenile Delinquency matters. While serving on the District Court Bench, he presided well over a hundred jury trials.

Prior to his appointment to the District Court Bench, he was a Deputy District Attorney in the First Judicial District for over nine years. During his tenure with the D.A.’s office, Justice Boatright tried everything from first degree murder cases to third degree assault cases. Prior to being appointed as a Deputy D.A., he was in private practice for approximately a year and a half with the firm of Boatright and Ripp.

Justice Boatright was born in Golden, Colorado and graduated from Jefferson High school in 1980. He graduated from Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri in 1984 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Denver in 1988.

Justice William W. Hood, III

Sworn in as a member of the Colorado Supreme Court on January 13, 2014

Justice Hood was sworn in as a member of the Colorado Supreme Court on January 13, 2014, following seven years as a judge on the Denver District Court. In 2014, the Colorado Chapter of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers gave him its Distinguished Jurist Award. In 2011, he received the Denver Bar Association’s (DBA’s) Judicial Excellence Award.

Before moving to the bench, Justice Hood was a litigation partner at Isaacson Rosenbaum P.C. in Denver and served as a prosecutor for ten years in Colorado’s 18th Judicial District (encompassing Arapahoe, Douglas, Lincoln and Elbert Counties). At different times, he was a chief trial deputy and the chief appellate deputy.

In 1990, Justice Hood graduated from the University of Virginia School of Law where he was a member of the Virginia Law Review. In 1985, he received his B.A. magna cum laude with honors in International Relations from Syracuse University and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa.

Justice Richard L. Gabriel: date of Judicial Appointment: June 23, 2015 by Gov. John Hickenlooper

Justice Gabriel was appointed by Governor John Hickenlooper to the Colorado Supreme Court June 23, 2015. Judge, Colorado Court of Appeals (2008-2015). Private practice (1988-2008): Partner (1994-2008) and Associate (1990-94), Holme Roberts & Owen LLP, Denver, CO; Associate, Shea & Gould LLC, New York, NY (1988-90). Practice focused on commercial, intellectual property, probate, and products liability litigation, all including appeals. Also served as City Prosecutor for Lafayette, Colorado. Judicial clerkship (1987-88): Law clerk, Hon. J. Frederick Motz, U.S. District Court, District of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

B.A. cum laude in American Studies from Yale University (1984); J.D. from University of Pennsylvania School of Law (1987). Articles editor, University of Pennsylvania Law Review (1986-87). Winner, Keedy Cup Moot Court Competition (1987).

Admitted to state bars of New York (1987) and Colorado (1990) and to numerous federal district and appellate courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. Member: American, Colorado, Denver, and New York Bar Associations. Honors: Champion for Children, Rocky Mountain Children’s Law Center (1997); Forty Under 40, Denver Business Journal (2002); Richard Marden Davis Award, Denver Bar Foundation (2002); Colorado Super Lawyer (2007-08); Chambers’ Leading Lawyers for Business (2007-08); Intellectual Property Lawyer of the Year, Law Week Colorado (2007); named as a Lawyer of the Year, Lawyers USA (2007); Denver Bar Association Award of Merit (2014).

The outcome rests in these seven people’s capable hands—one way or the other. The question is presently open as to whether the Colorado Supreme Court will choose to review the appellate court’s decision in Martinez v. COGCC. If the high court does review it, will it let the decision stand or will it reverse the appeals court ruling?

A reversal of the appeals court decision would allow the COGCC to continue to permit oil and gas activity using its traditional ‘balanced’ interpretation of its legal directive. If the supreme court decides not to review the decision or if it rules in favor of the appeals court decision, either action could result in the COGCC being forced to change how it permits oil and gas activity to comply with the appeals court’s ruling on its directive, or it could set off further legal action on both sides.