Fed is likely to raise its key rate two more times – Dallas Federal Reserve

The last time the world’s central banks diverged on policy came as the Fed increased its key rate in December 2015. It’s happening again.

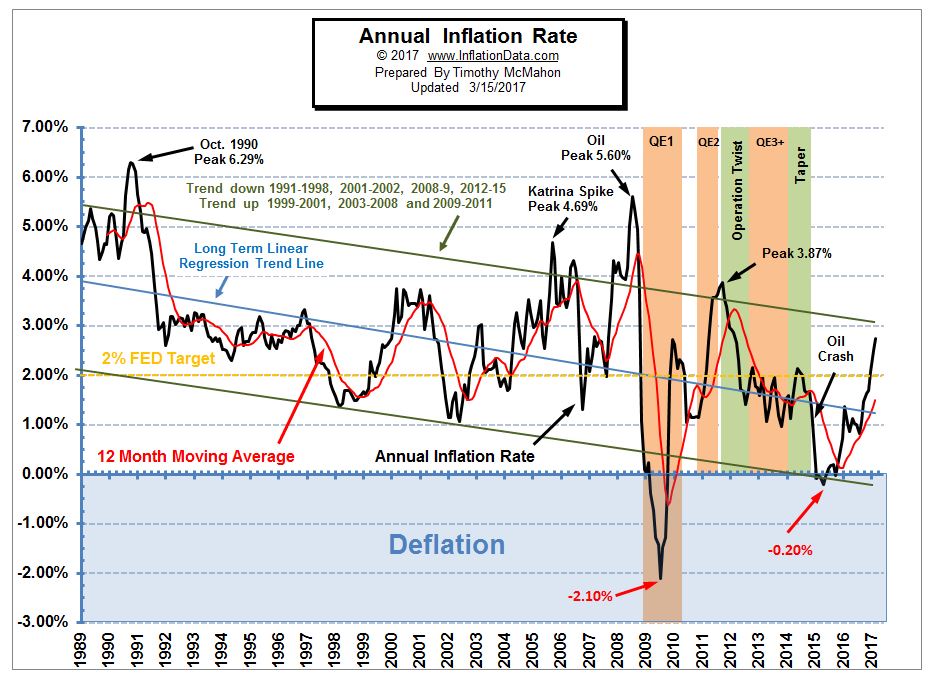

The U.S. Federal Reserve continued its policy of quantitative tightening last week by raising the key rate 25 basis points, and appears ready to increase the rate further this year. If the U.S. workforce stays near full employment (unemployment under 5%) and inflation continues to head toward 2%, the Fed could potentially raise the key rate two more times this year, Dallas Federal Reserve Bank President Robert Kaplan told Reuters.

“Now that we’ve [raised rates again], I think that we’ve got the benefit of a little time here to see how the economy unfolds,” he said. “I plan to take advantage of that to assess how the economy is unfolding and be prepared to make a judgment as we head toward the next meetings.”

Kaplan said that two more rate hikes this year is a “reasonable” base case as long as economic indicators continue to hold.

“We are still accommodative and I think it’s very appropriate for us to be accommodative,” he said. If inflation rises above the Fed’s 2% target for a brief period, it is not going trigger faster rate hikes as long as it is not a persistent trend, he said.

Though the current rate of U.S. unemployment, at 4.7%, is below the level historically thought to be consistent with full employment, Kaplan said he does not believe it will generate undue upward pressure on prices.

World’s central banks chasing different objectives

Since the U.S. Federal Reserve’s decision last week to increase its key rate, a number of other central banks have also been issued their most recent key rates.

Many central banks are beginning to diverge from the Fed’s path due to commodity prices and conflicting interests, a report from Stratfor said earlier this month.

- The People’s Bank of China announced that it would follow suit with the Federal Reserve and increase interest rates which is likely to help mitigate capital flight from the country;

- The Bank of Japan chose to leave its policy unchanged;

- Swiss National Bank – unchanged;

- Bank of England – unchanged;

- The Bank of Canada indicated that it will keep its key rate at 0.50% for the remainder of this year, and likely through a portion of 2018.

Canada’s central bank confirmed that “subdued growth in ‘wages and hours worked’ continue to reflect persistent economic slack in Canada, in contrast to the United States,” the bank said.

The Bank of Japan favors a weaker currency compared to the United States because it makes exports more attractive to holders of other currencies. Switzerland has faced a perennial struggle to keep the franc’s value down, and the United Kingdom is attempting to stimulate exports making a stronger currency counterproductive, said Stratfor.

“Inflationary trends appear to rest on weak foundations,” said Stratfor. “The first sign of the turnaround in prices emerged last year in China, where falling commodity prices since 2012 had created an ongoing drop in production prices, which manifested around the world as consumers bought cheaper Chinese products. As commodity prices stabilized last year, driving Chinese production prices up for the first time in four years, they helped create the reflation narrative that seized global markets.

“But inflation driven by commodity price increases is less sustainable than that caused by wage pressures. If commodities reverse, the inflationary gains would rapidly evaporate, leaving central banks back where they started at the start of 2016.”

Commodity prices could quickly turn the inflationary pressures seen in other parts of the globe, and with oil prices down so far this month, central banks around the world may take a different approach from the U.S. Federal Reserve.

The last time the world’s central banks diverged on policy was when the U.S. Fed increased rates in 2015, a decision that led to a two-month period of “drama in global financial markets,” points out Stratfor, with sell-offs hammering weak points such as Italian banks and Chinese capital outflows markedly increasing.

“That period came to an end after central banks apparently coordinated their policies to reduce the divergence,” said Stratfor. “This time around, with strong pressures pushing the actors in different directions, such an alignment would be harder to achieve.”