Congress expected to vote to lift crude oil export ban; economists worry about low inflation

An end to the more than 40-year old crude oil export ban could soon be approaching. Members of Senate this week are expected to include a provision that will lift the export ban as part of the fiscal 2016 spending bill, aides from both parties said. The spending bill is expected to be decided this week before Congress goes on break for the holidays.

In exchange for removing the export ban, Democrats are asking that at least a five-year extension be added to tax credits for wind and solar power, as well as a permanent authorization for the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Some Democrats from the Northeast are also floating a tax credit for independent domestic refineries, especially those that could be hit if the export ban is lifted.

Following the United Nations’ COP21 Paris climate agreement that occurred over the weekend, adding in the tax credits for renewable energy in exchange for lifting the ban could be the push needed to convince senators with environmental concerns that allowing exports will not stifle growth in the renewables sector.

Republicans have signaled that they might be willing consider the tax credits in exchange for allowing crude oil exports, but Senator John Cornyn (R-TX), the chamber’s second-ranking Republican, indicated that tension remains. “Democrats keep upping the price,” said the senator, but lifting the ban “is still in play.”

Industry leaders in the oil sector hope that lifting the crude oil export ban would help U.S. companies navigate the current market more easily. “U.S. producers are getting disproportionately impacted by low oil prices because the ban is in place,” said John Hess, CEO of Hess Corp. (ticker: HES).

Crude futures still reeling from 10.9% drop last week

Despite talk that U.S. producers may soon be able to export their crude, oil prices remain at seven-year lows following OPEC’s December 4 meeting in Vienna. Crude futures fell $4.35, or 10.9%, on the week to $35.62 at close on Friday, December 11, when OPEC announced that the group would remove its production quota entirely.

The continued drop in crude oil prices also triggered a selloff of junk bonds, many of which were issued by energy companies. Oil majors like ExxonMobil (ticker: XOM) and Chesapeake Energy (ticker: CHK) saw their stocks fall 6% and 9%, respectively.

[email_signup label=”Sign Up for Closing Bell – our Free, End-of-Day Oil & Gas News Report”]

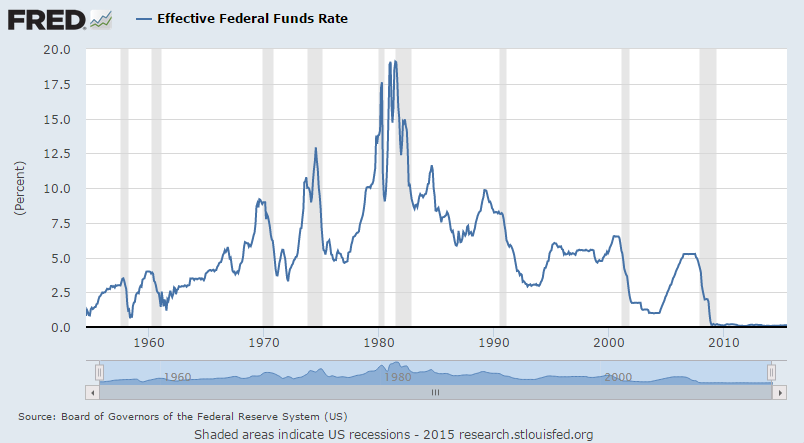

Federal Reserve expected to raise rates for the first time since 2006

Along with the steep decline in crude oil prices, natural gas also shed about 14% of its value following the OPEC decision, closing Friday at $1.88 at Henry Hub. Lower commodity prices are effecting the wider market ahead of the Federal Reserve’s final meeting for the year, in which the Fed is expected to raise its key interest rate for the first time in nine years.

“The withdrawal of Fed policy creates these hissy fits,” Peter Boockvar, chief market analyst at The Lindsey Group, told Barron’s. “It’s pretty clear everyone expects it to happen, and the decision comes with so much baggage.”

Volatility swept world markets last week ahead of the Fed’s decision, with Asian stocks trading in the red, but European stocks recovering from their worst week in almost four months, reports BNN. On Friday, the Dow sank 1.8% and the S&P 500 declined 1.9%.

“Nerves are fraying ahead of the Fed’s expected decision to lift U.S. rates on Wednesday. And this might just be a foretaste of what’s to come if the market does not like what the Fed has to say on Wednesday,” said Steve Barrow, head of G10 strategy at Standard Bank in London.

Some question remains about whether or not the Fed will raise rates at its meeting this week, however. The Federal Reserve’s mandates include full employment, and a target inflation rate of 2%. With unemployment down to about 5%, a figure close to estimates of full employment, but inflation remaining below 1% members of the Fed are split on raising rates.

Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen said in a speech in September that “significant uncertainty” about her predication that inflation would rise exists. Yellen faces dissent from Fed officials who want to keep interest rates near zero until there is concrete evidence of inflation rising, reports The Wall Street Journal.

“I am far less confident about reaching our inflation goal within a reasonable time frame,” said Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Fed. “Inflation has been too low for too long.”

Concerns over low inflation persist across the globe

Concerns over stagnate inflation are hardly unique to the U.S., with inflation in many of the world’s major developed economies falling flat. The Eurozone has an annual inflation rate of 0.1% and 1.9% growth in output from a year ago; the U.K. has -0.1% inflation and growth of 2.3% over the same period; Japan is looking at 0.3% inflation and 1.1% growth; and the U.S. struggles to push inflation above 0.2% while growth sits at 2.2%.

Low oil prices have certainly contributed to lower inflation, but even when looking at core inflation, which excludes volatile commodities like food and energy, inflation still sits at just 1.3%.

A variety of various issues have been blamed for relatively unmoving inflation rates. Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke pointed to stingy fiscal policy as one reason, saying the central bank can only do so much to stabilize the economy if lawmakers are working against the Fed.

A new theory from former Bank of Japan governor Masaaki Shirakawa, points to demographic issues. According to Shirakawa’s theory, aging populations in countries like Japan have unleashed deflationary forces by lowering expectations of growth, straining the government’s budget and putting a growing proportion of consumption in the hands of older people who draw on savings rather than younger wage earners.

In 2014, a trio of economists at the International Monetary Fund endorsed many of Shirakawa’s hypotheses, arguing there are “substantial deflationary pressures from aging” and that “this applies not just to Japan, but also to other countries with aging or declining populations.”

Shirakawa’s theory also points to sentiment playing a large role in inflation rates. When businesses and workers expect high inflation, they try to command higher prices and wages, respectively, helping push up inflation. When they expect prices and wages to fall, they slow spending, which would help push down inflation.

Unfortunately, expectations for inflation are likely to remain low said Evans. “I talk to a wide range of business contacts, and virtually none of them are mentioning rising inflationary or cost pressures,” he said. “No one is planning for higher inflation. My contacts just don’t expect it.”