Remember the outrage when a handful of U.S. oil refineries closed in 2020?

If you don’t, that’s because there wasn’t any outrage. Oil and gasoline prices were blissfully low and the COVID-19 pandemic dominated the news. Hardly anybody noticed.

Energy investors certainly did, however, because 2020 was one of the worst years in history for energy producers. Exxon Mobil notched the first loss in its history, a gigantic $22 billion write-off. The five biggest U.S. oil refiners — Marathon Petroleum, Valero Energy, Exxon Mobil, Phillips 66, and Chevron — lost a combined $43 billion as COVID shutdowns worldwide produced an epic plunge in oil prices and energy demand.

This data on expected global demand for oil versus the actual demand shows how badly the oil industry crashed in 2020:

Source: International Energy Agency

These days, many Americans blame President Biden for soaring gasoline and household energy prices because he has trash-talked fossil fuel energy as part of his push for a green energy transition. But economics, not politics, explains most of the current price surge, and the 2020 energy wipeout set the stage for painfully high prices now.

Biden himself seems to lack a solid understanding of the economic fundamentals determining prices now. On June 15, he sent strongly worded letters to seven big oil refiners — the five biggest plus BP and Shell — complaining about the record profits they are now notching in addition to a tripling of profit margins during recent months.

“Your companies and others have an opportunity to take immediate actions to increase the supply of gasoline, diesel and other refined product,” Biden wrote. “Your companies need to work with my administration to bring forward concrete, near-term solutions that address the crisis.”

Exxon issued a terse statement in response to Biden’s inquiry, saying it has continued modest investments in refining capacity. It also said Biden could ease some regulations on an emergency basis, which would make it easier to move fuels around in the refining process. Exxon also encouraged “clear and consistent policy” on energy resources, a reference to permitting, leasing, and regulatory policies that change from president to president and discourage investors who don’t want to get trapped in a stark policy shift.

Biden is basically asking energy firms to restart refineries deemed to be money losers during the depths of 2020 while also asking those firms to invest in more capacity with no guarantee prices will stay high in a way such that they’ll earn a return on that investment. In fact, Biden is implicitly asking energy producers to add capacity at the expense of their own profitability, because more capacity would bring prices down. If the government could guarantee prices would stay above a certain level, guaranteeing profits, the industry might produce more. But guaranteeing high prices wouldn’t solve Biden’s problem with voters — and would probably make it worse.

The American Petroleum Institute senses an opportunity to push back on Biden’s green energy push. On June 14, the industry group sent the White House a 10-point list of actions it says would ease the current crunch. At least half of them would upend Biden’s green energy goals, putting Biden at war with the progressive wing of his party. There’s little overlap, at the moment, between what Biden is asking for and what the industry is offering. And Biden is generally opposed to executive actions that might bypass negotiations but fail to hold up in court.

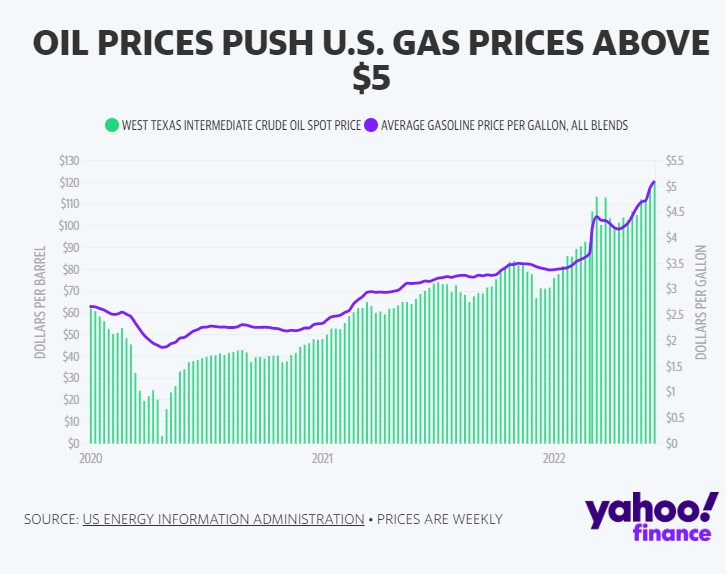

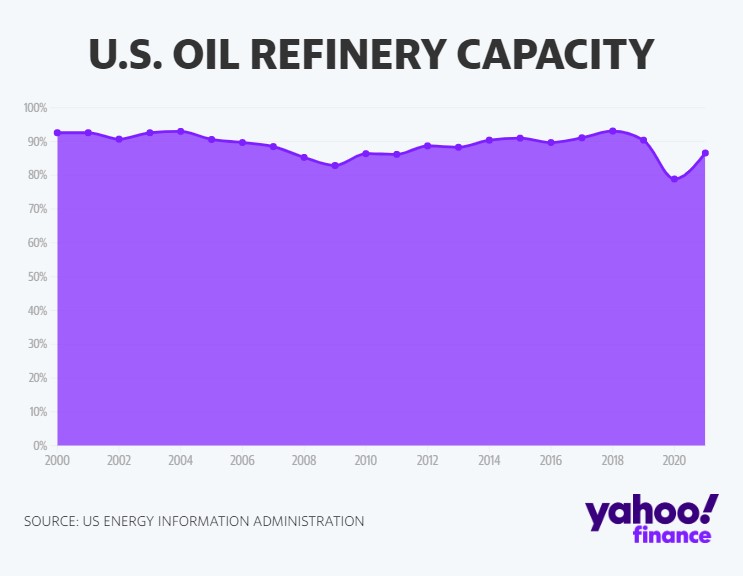

In his letter to the seven refiners, Biden correctly noted that global refining capacity has fallen by 3 million barrels a day since 2020, which is about a 4% decline. In the United States, refining capacity has fallen by about 1 million barrels per day, or roughly 6%. With global demand for oil and oil products nearly back to pre-pandemic levels, that marginal refining shortfall is enough to create bottlenecks and jack up prices.

It’s also indisputable that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered what may be the most serious globally energy crisis since the 1970s. Sanctions on Russia will probably remove about 2 million barrels of oil per day from markets, about 2% of the total. Many Americans think that U.S. “energy independence” means the United States doesn’t depend at all on foreign oil, but that’s not true and has never been true. Virtually every country in the world must accept oil prices set by supply and demand in the global market.

And while Biden has overused the phrase “Putin’s price hike,” he does have a point. From Biden’s first day in office to Feb. 23, 2022, gas prices rose from $2.45 a gallon to about $3.60 a gallon. That’s a gain of $1.15 during a period of 13 months. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, prices have soared to about $5.10, a gain of $1.50 during a period of four months. Soaring prices come from actual reductions in oil supply and from fear that an adverse turn in the war could cause a much more acute supply problem. Nothing else has happened during the last four months that would explain those dramatic price hikes.

An end to Russia’s war against Ukraine would be the fastest way to bring energy prices down — and energy producers surely realize the war will end someday, denting profits. But prices may drift down as the Russia-Ukraine war drags on. The U.S. Energy Information Administration expects U.S. refiners to be operating at nearly full capacity for the rest of 2022, with gasoline and diesel prices drifting down during the summer and fall. In the EIA’s latest forecast, it expects gas prices to fall back below $4 in 2023.