Aug. 8 deadline looms

Ballot proposal 78 could reduce the surface area available for drilling in Colorado by 90%: COGCC report

While the economic impacts would not likely put the state into a recession, they would reduce the state’s GDP by 3.4% over a 15-year period: Univ. of Colorado study

Colorado has become a hot-spot for political issues in the oil and gas industry.

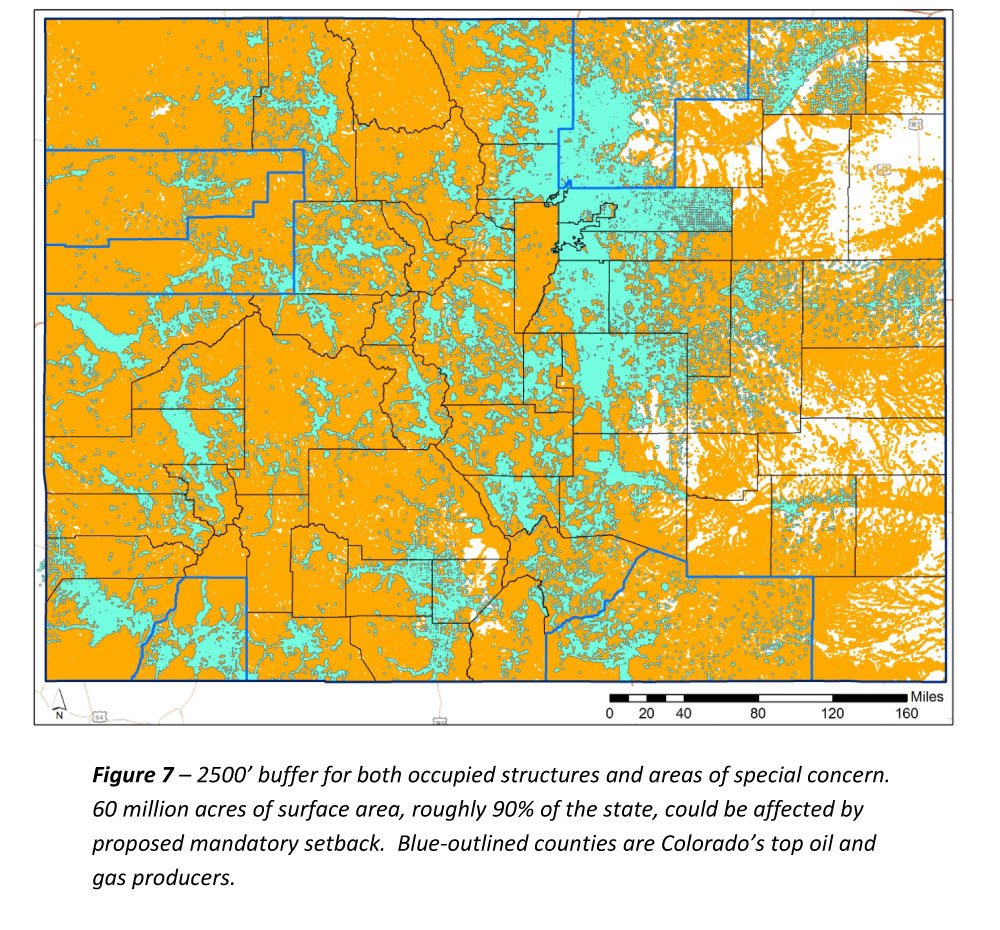

Several counties, including Fort Collins and Longmont, saw moratoriums on hydraulic fracturing struck down earlier this year, but environmental groups in the state continue to try and limit drilling. Currently, anti-fracing groups are proposing a ballot initiative to amend the state’s constitution to require a 2,500-foot mandatory setback for oil and gas development facilities, a move which would reduce the surface area available for drilling by 90%, according to a study from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC).

The initiative has until August 8th to collect at least 140,000 signatures to get the proposal onto the ballot in front of voters, a prospect that Wells Fargo puts at a “better than 50/50 possibility.” If the proposal does make it in front of Colorado voters in November, the bank believes it is unlikely to pass, but the wording of the amendment could prove powerful.

“When the average person reads an amendment that says push back drilling 1,500’ further from schools, they will tend to believe it’s a good idea. Just significant risk in our opinion,” the bank said in its summary.

Colorado GDP growth could slow by 3.4% over the next 15 years if initiative passes: Univ. of Colorado

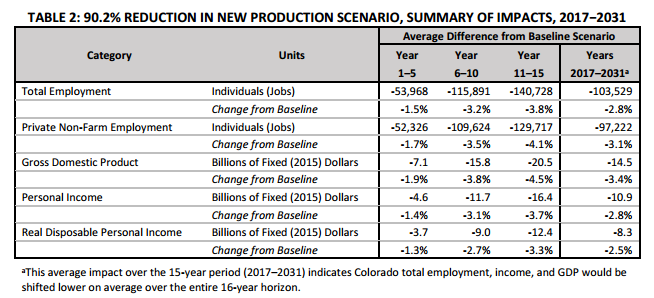

If ballot initiative 78 makes it onto the November ballot and passes, the state of Colorado could face very real economic consequences, a new study from the University of Colorado found. The study, which looks specifically at the economic impact of the 2,500 foot setbacks, concluded that a 90% reduction in new production beginning in 2017, along with the current state of the oil and gas industry would “result in a lower real GDP by an average of $7.1 billion and 54,000 fewer jobs in the first five years (2017-2021), and a lower GDP by an average of $14.5 billion and 104,000 fewer jobs between 2017 and 2031.”

The University of Colorado study found that, while the economic impacts would not put the state into a recession, they would reduce the state’s GDP by 3.4% over the 15-year period the study covered.

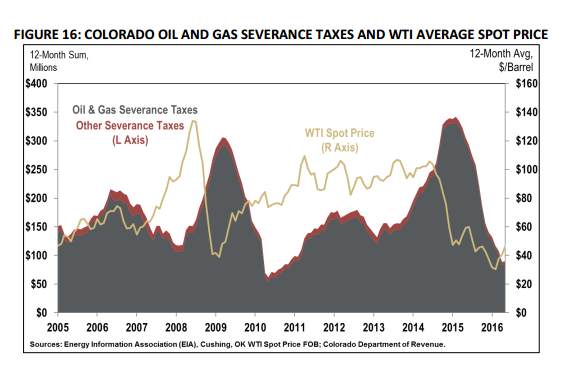

In 2013 and 2014, the Colorado Department of Revenue reported $170.6 million and $330 million, respectively, in severance taxes from oil and gas operations. In 2015, severance taxes dropped to $134 million, and the trailing twelve month sum as of May 2016 was just $84.2 million.

In June 2016, the Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB) estimated that severance taxes will decrease 77.6% in fiscal year 2016, to $63.0 million. OSPB’s forecast for fiscal year 2017 is expected to rebound to $89.2 million – an increase of 41.7%. Fiscal year 2018 is projected to increase to $175.9 million. Colorado Legislative Council estimated fiscal year 2016 severance taxes (including interest earnings) at $66.2 million, dropping 76.5% from 2015. Severance tax revenue is expected to rebound slightly, to $77.1 million in fiscal year 2017, before increasing 112% in fiscal year 2018, to $163.5 million.

For its own part, the CU Business Research Division estimated the public revenue stream from the oil and gas industry totaled $1.2 billion to state jurisdictions in 2014. As a point of comparison, for fiscal year 2014, the governor requested a total budget of $24.1 billion.

“The majority of public revenue comes in the form of property, income (personal), and severance taxes; public land leases; and royalties,” the study said. “Oil and gas property taxes exceeded an estimated $400 million in 2014. Severance taxes paid by the industry totaled $330 million in 2014. The industry also paid $315 million in royalties, rents, and bonus to the federal government in 2014 (less than half is returned to Colorado), and nearly $160 million in state royalties, rents, and bonuses.”

Of the state severance tax revenue, 50% goes to the state trust fund and 50% to the local impact fund, according to an earlier study also conducted by the University of Colorado. Funds from the state trust fund are then allocated to a fund used to finance loans for state water projects, administrated by the Colorado Water Conservation Board and an operational account used for programs administrated by the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. The local impact fund share, meanwhile is distributed either to local government grant projects (70%) or directly to local governments (30%).

If ballot initiative 78 is passed, Colorado stands to lose a major driver of economic growth. With a substantial portion of the budget coming from severance taxes, and the industry providing jobs for thousands in the state, creating a constitutional amendment that would permanently reduce the amount of land available for oil and gas development by 90% will negatively affect the state’s economy—and damage its reputation as a business-friendly energy-focused state looking for future capital investment.

Political risk in the United States

In June, the University of Colorado Denver Business School’s Graduate Energy Management program hosted a seminar that discussed political risk in the energy sector and how companies view and deal with it.

The two key expert panelists were Noble Energy’s Director of U.S. Onshore Government Relations and Communications Brian Miller and Halliburton’s Director of State and Local Government Affairs Stephen Flaherty. They discussed the process of engaging with foreign governments in places like West Africa, Israel and other areas of the globe. The two panelists also discussed working at the state level, working with regulators and the importance of “helping regulators understand the full impact” of the proposed regulations they write.

But the idea of regulation of an industry by a qualified state agency that works closely with industry players in the process of enforcing, mediating and interpreting rules is a far cry from an amendment to the constitution that essentially stops development.

Black swans

One question that was asked: what are the black swans the industry is facing?

Flaherty said that 10-15 years ago oil and gas companies had the ability to meet with the environmental stakeholders and create rules that both sides could agree on.

“We could unify together to craft public policy that would protect the environment and also produce resources. But today we face a global movement called “Keep it in the Ground” so we’ve lost a partner. They are not willing to come to the table so long as the drill bit is turning. It’s no longer about policy, it’s about politics,” Flaherty said.

Both men emphasized the importance of energy companies and their employees engaging the public via social media to emphasize the economic benefits that come from developing oil and gas in Colorado and other states.

Karen Crummy, director of communications for Protecting Colorado’s Environment, Economy, and Energy Independence, told Oil & Gas 360® that there is no available update on signature count for initiative 78. Both Crummy and the Colorado Dept. of State said “we won’t know until Aug. 8.”

A tricky legal battle lies ahead if the initiative passes

The last time ballot initiatives reared their head in Colorado, the state’s governor, John Hickenlooper, bargained a compromise in which the initiatives were removed, and a task force was formed to find a compromise between all sides. After more than a year of bargaining, COGCC approved two new rules based on the task force’s recommendations.

This time around, a compromise is less likely Special Counsel David Steinberger with Feldmann Nagel, LLC, told Oil & Gas 360®. “I don’t think they could do another task force. The parties seemed dissatisfied with the last one,” said Steinberger, who represents clients on issues including environmental and natural resource matters.

Steinberger believes there is a good chance that the initiative will make it on the ballot, and once that happens, it will be a matter of who can win the hearts and minds of voters.

“If it does pass, what happens next is an open question,” he said. “Most people would think of filing a takings claim, but that becomes a more difficult argument when you consider this is a constitutional amendment.” A takings claim is one that addresses private property being taken for public use without just compensation.

“Maybe there’s a class-action lawsuit, but who do you sue? This isn’t something being passed by the legislature, it’s a constitutional amendment being voted on by the people of Colorado. If it passes, you may need to wait for the economic impact to hit, and then for a new ballot initiative to amend the constitution again.”